I have this strange hobby: whenever I see an old house or building in my town about to be torn down, it becomes my obsession. I take photos of the process, and to the best of my ability, try to be there for the destruction. I am sentimental about old things, and I desperately want it all to be preserved.

Why write about this today? Because each of you are building something. You are a writer or creator, and there is a message or story inside of you that needs to be expressed. This process helps you understand yourself and the world better. And it has the potential to help others understand themselves and the world better too.

When a reader comes to your work, there needs to be a sense of trust of where you will take them. That they are safe in your hands, yet there is a sense of potential of where you may go, even if it is surprising and unexpected.

In what you create, you hope that it is preserved. That your ideas and stories and writing won’t fade away. That they are filled with potential for who it will reach, how it will grow, and the impact it may have. The goal? That your work is sustained over time. And that you as a writer can persist and continue to create.

Invariably, this is about creating that special place of trust and potential.

Whenever I see an old building about to be destroyed, I think about the loss of stories of those who lived there, and the loss of potential of future generations who could have experienced it as well. Sure, it’s all just wood and brick and nails, but they represent so much more.

Today I want to take you on a little journey, and end with some conclusions I have come to about how we preserve our ability to create. Let’s dig in…

Invest in Possibility and Connection

A few years back an old movie theater in my town was under threat to be destroyed. At the time, I began showing up to every planning board, zoning board, and historic preservation meeting. Not just those about the theater, all of them, including the mundane ones where someone wanted to expand their driveway 5 feet. I just sat there, listening, seeing how the process worked.

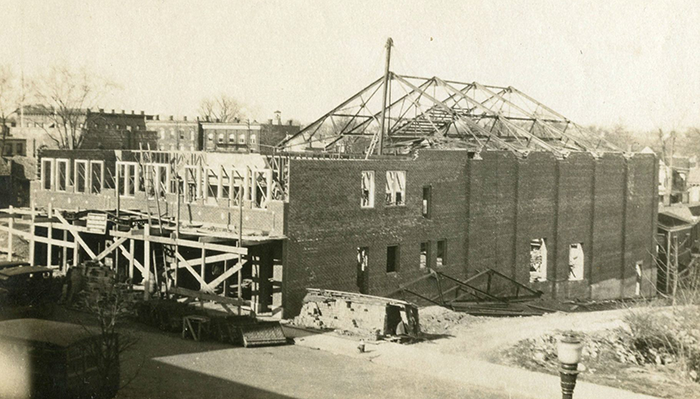

Allow me to share the history of this theater in photos. Here it is being built in the 1920s:

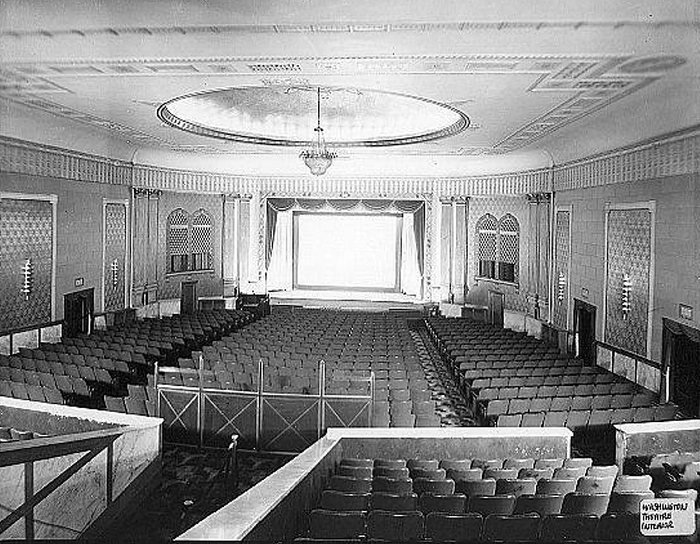

This is what the finished theater looked like inside:

Here is the outside as it looked a few years back:

This is the process of destroying it:

This is the new building being finished in its place. It will have dozens of condos in it, plus a couple retail stores:

And this is the last remaining brick from the original theater, which I saved and display here in my studio as a reminder:

Here are other old buildings that have been destroyed in my town. For each of these, I would often stand outside for hours watching them be torn down:

You may notice small details in each of these, such as the third floor room painted in a rainbow of colors signifying a child’s playroom, or the large world map painted onto a wall of a room that may have been a home classroom, or the home office of a history buff.

For each of these, a new home now stands, and on larger lots, 3 or 4 homes have been built in the place of one.

Preserve What You Create – And Support Creators You Love

In the past, I had often considered that it takes years to create something and a moment to destroy it. And of course, that can be true in some case.

But in my hobby of obsessing about old buildings here in town, I noticed something surprising: it often takes years to destroy something. Thousands of actions of neglect. Ignoring threats that could take away a beloved place. The lack of will to collaborate and take a chance to preserve something.

Some of it is simple: never maintaining or repairing a structure, until the wood is rotten, the bricks crumbing, and the systems outdated. These inactions allow the structure to get to the point where saving it becomes a massive undertaking because of how dilapidated it had become.

I see this happen with creative work as well. When someone barely shows up to create. When they do the minimum to share it. When they continue to have big aspirations of what could happen with their creative vision, but it gets overshadowed by other priorities.

Of course, sometimes, that is simply life. Tending to our families, our jobs, or physical and mental health, and a vast array of other responsibilities can take priority, and for good reason. But other times we simply don’t tend to our creative work out of distraction. These small moments of neglect can add up. Sometimes that is the books we haven’t written, the essays we haven’t crafted, the relationships with colleagues we never strengthened, and the habits we never developed to create and share with vigor.

Likewise, sometimes we don’t do what is required to support the work of writers and artists we admire. We don’t show up to their events, we don’t let them know how much their work meant to us, we don’t take actions to help ensure their work persists.

Earlier this week I saw a Facebook post of a homemade candy store that has operated in a nearby town for 65 years was closing. Of course, there were loads of comments about how sad this was, and they questioned how it could possibly be happening. But then someone posted honestly, “I always wanted to go in here. Never made it.” Then another replied back, “Same here, only passed it a million times.” Preserving what we create and the writing and art that we admire takes effort. And I think that effort is worth it.

So why am I sharing these stories with you, a writer or artist who probably doesn’t live in my town or anywhere near it? It is this…

Support those who create before they are gone. Is there an author whose work you appreciate? Send them a thank you email. Is there a local bookstore you love, but you just don’t get there often enough? Take a trip this week and set the intention to spend a certain amount of money to support them. Is there a local nonprofit in the arts that you admire? Go to their website and see how you can support them, even if it is just showing up for an event or spreading the word.

For your own work, it can be easy to feel that the world has changed, and that the marketplace is now overcrowded; that there is no room for your art to find a place.

But you have a unique voice in the world, and you can create something truly special in your writing and art that will inspire someone. It is a place filled with a sense of safety and potential.

I want your creative vision to persist, and for your writing to reach more people. With that goal in mind, if I could encourage you to take two actions this week, it would be this:

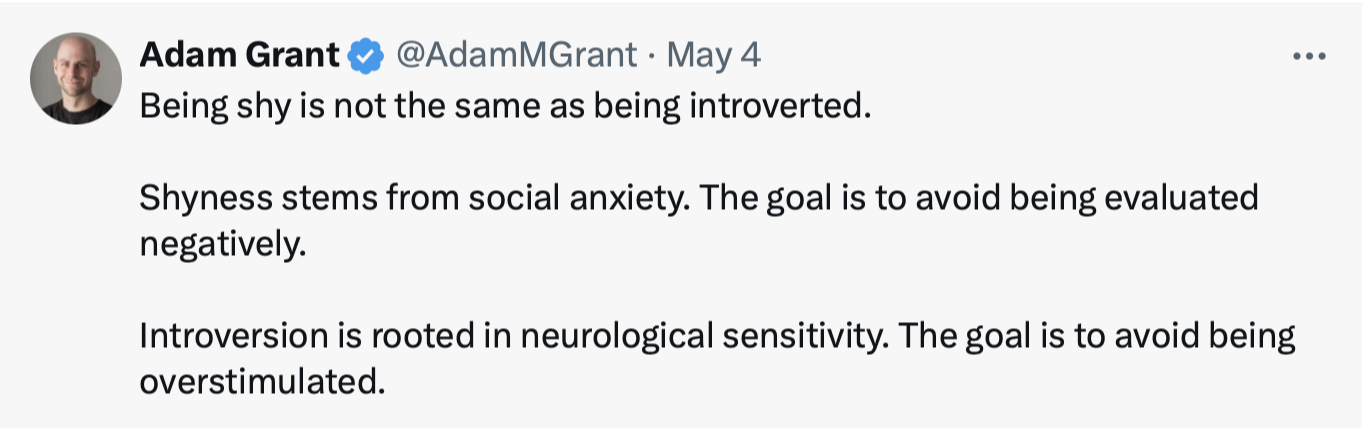

- Make more time to create, less time to consume or react. Set your own intentions for the week instead of being swayed by scrolling in a feed, the latest trend, or the 1,000th “best practice” you are told you have to do.

- Make more time to connect with one person this week. Email a fellow writer who you haven’t spoken with in a while. Ask a reader a question. Do something to initiate a new connection. That action is often much simpler than we imagine. A smile. An email. A question. Don’t exhaust yourself vying for more social media followers, instead focus on meaningful connections with the writers, creators, and readers who inspire you.

Create a Support System for Your Creative Work

Too often, when building our creative work, we give up too soon. It’s soooooo easy to feel that we have failed when we have just begun. Often the sense of “failure” comes in the form of silence from others. And it’s so easy in those moments to dim your flame a little bit. To lower your voice. To write… a bit less often. To be more hesitant to share.

Yet we don’t realize how much opportunity still awaits. Even if we are in the midst of cognitive dissonance that says “But I expected something, and it didn’t happen. Isn’t that a sign I should stop?

I encourage you to keep going. Create a support system for your creative work. One that allows you to feel safe to create. This may include a physical space where you are free to explore without judgement, or to write without distraction. And while sometimes that may mean a private writing studio with a door that has a lock on it, more often it is a writer stealing 20 minutes at a cafe to write, or sitting in their car in a parking lot somewhere, finding a brief moment of focus on writing before they head home from work.

Don’t go it alone. Develop colleagues around your creative work — others who strive to create as you do, and who appreciate that aspect of your identity. If no one like this exists in your life now, then seek them out. Sometimes that means showing up to places (online or off) where creators come together. Other times it means just recognizing and supporting those in your life who create work that isn’t exactly like yours — but they believe in just as fervently as you believe in your own creative vision.

Invest in creative maintenance. Work to preserve what you create. Create the habits and systems to ensure that your creative work can persist. Sometimes that means establishing clear boundaries with those around you so that you can feel good about the place that creativity occupies in your life. Other times it means buying a backup hard drive, or simply dusting your writing desk.

Please let me know in the comments: what is one action you can take in the next week to support your own creative vision, or that of someone who inspires you?

For my paid subscribers this week, I shared a video where I discuss lessons from my most popular post ever, with 6 tips for reaching more readers. You can view it here.

Thank you for being here with me.

-Dan