I work with writers because I absolutely love how the lone creative vision of an individual can create so much. I remember when I was working with bestselling author Joseph Finder who talked to me about his books being made into big budget Hollywood movies. He described being on set of a film based on his book, starring Morgan Freeman and Ashley Judd, and how it took so many people to create a single scene. From the actors to the lighting directors, and sound people, set builders, director, so many other people. Yet to create that scene in his book, it just took him alone in a room, writing.

I love the idea of the lone creator — that you have this ability to create wherever you are, with whatever you have, in whatever context you are in.

But to realize the dream of where our creative vision may lead often takes collaboration. While the creative process can be solitary, the publishing and sharing process benefits from collaboration. In helping writers share their work, develop their audience, and launch their books, the social parts are often the most difficult. It’s common for a writer tell me that getting their work out there feels more difficult than creating it.

When you open yourself up to collaboration, your work is given new life, and a new ability to reach more people.

Today I want to explore this in three ways, with stories from a wide range of creative fields, including film, books, comics, and video. Let’s dig in…

Perception Vs. Reality of the Lone Writer

I often go back to this 2013 video from bestselling author John Green, where he talks about how people often hold him up as an example of a writer who can sell books without the help of collaborators, because he has a large audience on social media. He strongly disagrees, saying:

“I wouldn’t have any books to my name without the tireless and committed collaboration not only of my editor Julie Strauss-Gabel, my agent Jodi Reamer, my friends my family, everyone at Penguin, but also the collaboration of thousands of other people: copy editors, warehouse employees, programmers, people who know how to make servers work, librarians, and booksellers. We must strike down the insidious lie that a book is the creation of an individual soul laboring in isolation. We must strike it down because it threatens the overall quality and breadth of American literature… Without my editor, my first novel, Looking for Alaska, would have been unreadably self-indulgent, and even after she helped me make it better it wouldn’t have found its audience without unflagging support, now more than eight years on, from booksellers around the country.”

I’m always curious about the perception of how great work is created vs. the reality. Let me give you an example…

If you watch the movie Pulp Fiction, it ends with: “Written and Directed by Quentin Tarantino.” That has become a signature of all of Quentin’s movies. Except, that isn’t true. Pulp Fiction is cited again and again as one of the greatest films of all time, and often put within the top 10. So who actually wrote it?

Well, it turns out that Quentin wrote a lot of it, but his friend and collaborator Roger Avary wrote a lot of it too, including the entire middle sequence which has some of the most classic scenes and lines. I mean, they even won an Oscar together for Best Original Screenplay for the film:

As I dove into this by reading and listening to interviews, I was fascinated by the obfuscation. They spent a long time together writing Pulp Fiction, so how does Quentin justify excluding Roger from the credit? In one interview he says:

“Roger Avary came up with the idea. He’d written a whole script for a movie. I didn’t want to do the whole thing, only one section that fit into Pulp Fiction. I bought the script the way you’d buy a book to make into a movie, just to adapt the part that I liked. That was the scene when the boxer throws the fight and gets chased down by the other guy and they end up in a pawnshop with two guys who are serial killers.”

I mean, that sounds reasonable, right? Except when you hear more about how they collaborated on everything, and spent a long time together developing the film. In fact, the original idea for the film was that Quentin write and direct one sequence, Roger another, and a third filmmaker do the third. When that third guy missed his deadlines, Quentin sort of took over… all of it.

How did Roger lose credit? From what I can tell, Quentin simply said that he would like the credits to read a certain way, with the film ending with the card “Written and Directed by Quentin Tarantino.” I mean, wouldn’t that be nice for Quentin? He offered Roger credit in a “Stories by…” card which would include Quentin’s name, as well. They were friends, so Roger simply agreed.

The difference? A huge reputation shift because people commonly perceive that Quentin wrote Pulp Fiction all by himself. The fact that he is known for his dialogue underscores how removing the credit of another can impact how we view the film and creators.

The Idea Vs. The Execution

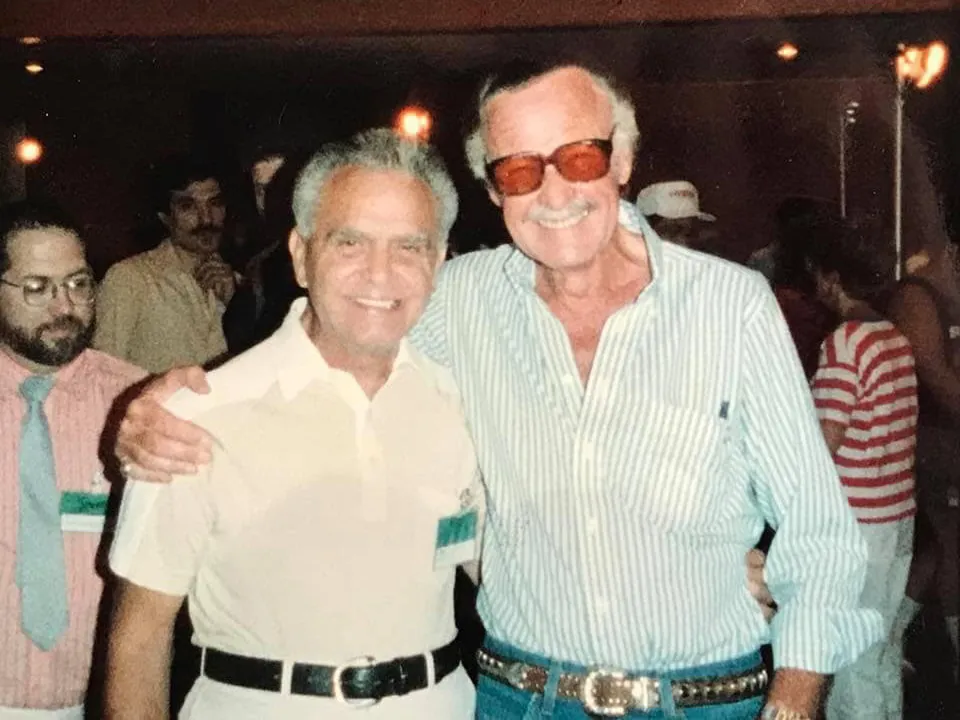

Remember all those Marvel movies that made an estimated $29.8 billion dollars based on characters created by Stan Lee? You know: Iron Man, Hulk, Avengers, and so many others. Um, well Stan didn’t create them alone.

It turns out that there is this guy named Jack Kirby who co-created many of these characters with Lee. In the comic book world, Jack is a legend. But in film and popular culture, we only ever hear about Stan Lee. Why is that?

(Jack Kirby and Stan Lee. Photo by Scott Anderson.)

I’ve read about this for years in books, articles, and interviews, and there have been legal cases for decades. To me, the most satisfying answer is a difference in perspective.

Why did Stan feel okay taking credit? He justified that the person who had the original idea is the true creator. What’s the problem with that for his collaborators? That sometimes, the initial idea was vague and unformed, and the illustrator (in this case Kirby) would do a ton of original creation as the character was developed, getting rid of ideas, adding new ones, and shaping the characters in profound ways.

It’s incredible to see the body of work that Jack Kirby created over the years — and the scope and pace of his output is just amazing. Yet… Stan is the household name.

The concepts here aren’t just emblematic of a broken system, where the comics industry had no guidelines or safeguards for credit or copyright. I’ve heard content creator Casey Neistat say many times that he firmly believes: “It’s the execution that matters, never the idea.” Or another version: “Ideas are common, execution is everything.”

Who is Casey? He became a sensation around a decade ago with his viral videos on YouTube, and by doing a daily vlog for years. He has 12 million YouTube followers and is a huge influence on many popular video creators.

He talks about how “most of his ideas are mediocre,” and has showcased how difficult the process is to turn an idea into reality. In his 534 daily vlogs, many of them were sharing the nuances of the creative process and collaboration.

We can see the exact same idea showcased in the film The Social Network, which is about the creation of Facebook. Two brothers came up with the idea for it and hired a programmer to take care of the tech side of it. The programmer then built it, launched it, and took total ownership, justifying it by saying the idea alone is feeble, and the execution was difficult, meaning he alone owns it.

Tools as Collaborators

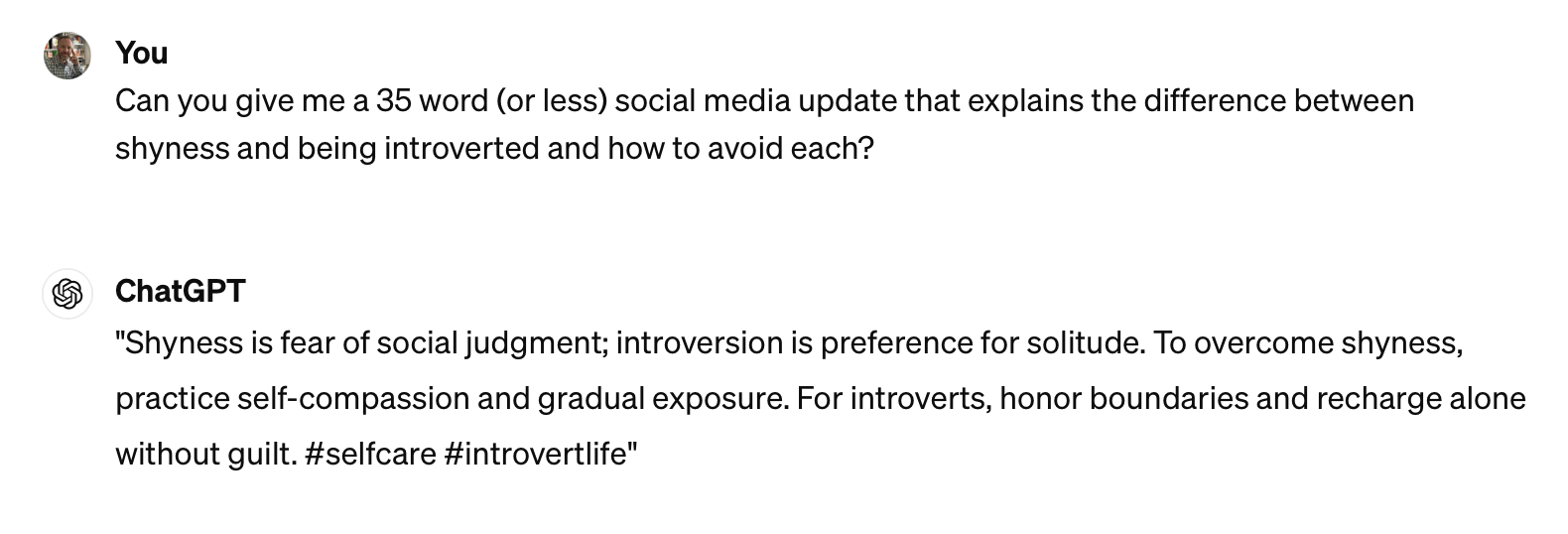

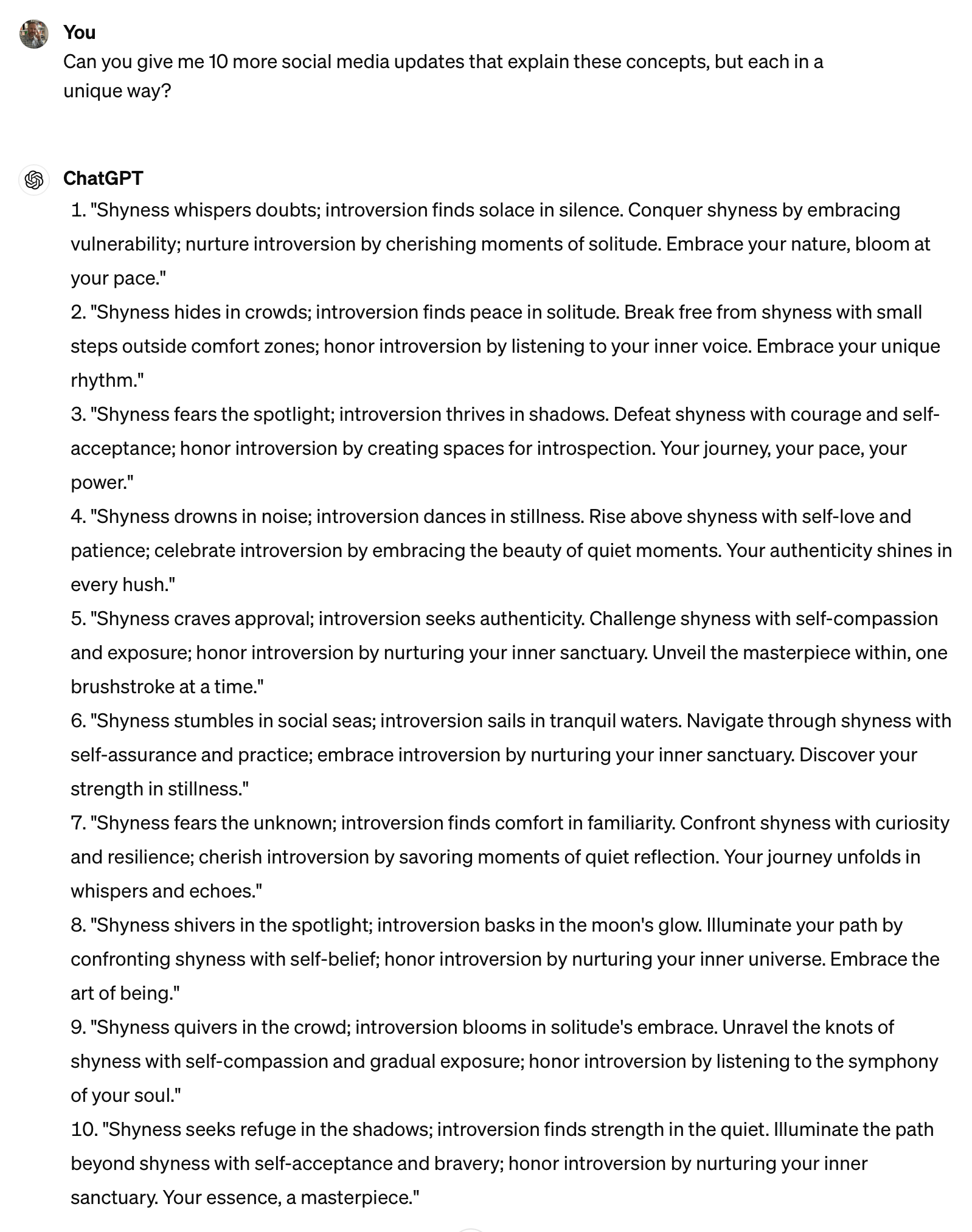

We are moving into a fascinating age where now the tools we use can also become our collaborators through AI.

I have a collection of old typewriters, but not once have they helped me craft a sentence, given me new ideas, or asked for me to “chat” with them:

When I spoke with author Dani Shapiro back in 2017, she talked about how the tool that most writers use to create — a computer — is also the source of their greatest distraction. I wonder how that may be compounded once AI is all around you — in your word processing program, on your computer, your phone, etc. What if you are always a millisecond away from just saying, “Hey AI, give me another way to start this paragraph?”

Where is that line between creator and collaborator?

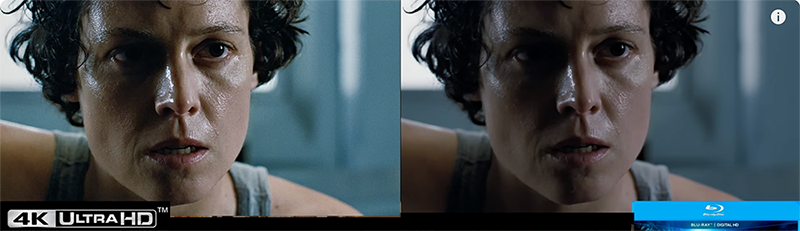

Just as a movie may have one writer on the title card, the reality is that many people may have contributed lines and ideas, including actors who ad lib ideas while shooting. The Empire Strikes Back has two writer credits and one “story by” credit. Yet none of those are responsible for one of the most famous lines of the movie, ad-libbed by Harrison Ford while filming:

Princess Leia: “I love you.”

Han Solo: “I know.”

It’s a line that perfectly sums up the character and reflects the nuanced relationship between the two of them in one of the most harrowing moments in the series. And of course, a line that is wildly better than what was in the script: “I love you, too.”

If you are struggling to consider how to move your creative work forward or how to share it with your ideal readers in a meaningful way, I encourage you to consider a collaboration. This does not have to be some big formal strategic process — simply reach out to one person. Ask for their help. Or flip it around and ask how you can best support their work. You will learn a lot in the process, and turn it from an act of isolation, to one of connection.

Thank you for being here with me.

-Dan