Does your business have vision? Do you have a goal for your career beyond stepping up a pre-determined corporate ladder?

Today I want to talk about the difference between having vision, and management.

Last week, I listened to Tim O’Reilly speak at a Publishing Point meetup in New York. He made a point about the need to be a visionary, and used Walt Disney as an example. That one’s business will always do well and adjust to the market if you are following a vision, not just protecting an established business model.

He was speaking to a room of publishers, but I think the point goes well beyond this one industry. For them, focusing on saving the existing book sales process may be a dead end. But if they follow a vision that focuses on writing, knowledge, sharing, and connection – they have a vibrant future regardless of form and business model.

When I was a teenager, I became obsessed with Walt Disney. I read every biography I could find on him, and remember scanning old articles on those horrible microfiche machines. So today, I want to explore the concept of why being a visionary will lead to business success, and do so by recounting a pivotal moment in Walt Disney’s career.

If you have 20 minutes, watch these two videos. They are the second & third parts of a three part series in which Walt Disney explains his plans for the Walt Disney World project in Florida.

Several things to notice:

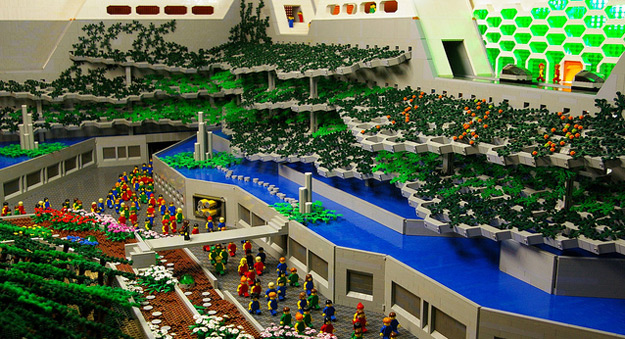

1. He describes EPCOT as the hub of the entire 27,400 acres. The Magic Kingdom amusement park is shoved into a corner compared to EPCOT.

2. EPCOT as we know it to day is NOTHING like what Walt Disney planned. He envisioned a true working city of the future. Celebration Florida even pales in comparison to what he had in mind.

3. EPCOT stands for Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow

4. He expected 20,000 people to live there, and industries to be centered there, all testing the latest technologies and innovations constantly.

Walt Disney was a visionary. He didn’t create a product, a business model, and then work hard to expand and protect it. He gave that task to managers. He looked at deeper reasons and further into what could be. He was always changing, always evolving, always growing. He pushed the Disney company into new territory.

He started in animation, moved to feature films, to television, to theme parks, and finally envisioned how we lived as a culture via EPCOT. At each step, he challenged us and created something of dramatically higher quality than we had come to expect. Theme parks were usually dirty places prior to his opening Disneyland. He received a great deal of resistance when he decided to open a theme park, people couldn’t imagine why he would want to open a place like that. They had no idea how far his vision went – how it eclipsed what we had come to expect from an amusement park.

Likewise, EPCOT was a bold enterprise – attempting to solve the problems of our cities. He would start from scratch, and build something entirely new. A living blueprint of the future that was always in the state of becoming.

Walt was focused on helping, not on entrenching. On expanding what Disney could do with their resources, not worrying about how to shove another Mickey Mouse doll into people’s lives.

This is how people grow, and ideally, how companies should grow. Not to think of ways to eek out another dollar from their customers, but think of new ways to help – to expand upon what was before, and move into new areas.

In some ways, once Walt Disney passed away, the company stopped growing. Sure, it EXPANDED, taking its intellectual property and expanding it into new markets and new products. They worked to integrate themselves into our lives, but in the same ways they always have. The Disney of today wants to change the way we live by putting a Mickey Mouse logo on everything you own. The Disney from Walt’s era wanted to change the way we live in ways that had nothing to do with cartoon characters.

Walt would have been pushing beyond toys and theme parks and TV shows. The closest comparison I can find today is someone like Richard Branson who is trying to create a consumer space airline. Disney would have been doing similar things – thinking so far beyond our expectations, that he challenges not only us, but his own company. I imagine Richard’s company gets worried when he has a new idea.

Why is Steve Jobs such a success? Because he scares the living daylights out of his own company. He pushes them, challenges them so much further than they ever would have on their own. Inherent in this is risk, and most companies try to avoid that.

Visionaries see the opposite – they see risk in standing still, in not growing. Not just personal risk, or financial risk, but cultural and human risk. That we – as human beings – are at risk when we stand still. We need to grow. It is what we owe our ancestors and future generations.

“Leadership” is a buzzword nowadays. When I say we need visionary leaders, I don’t just mean we need those with ideas to make speeches and motivate others. We need people who will get their hands dirty to build these things as well. That they will be as involved in tactics as well as vision. That you will see them in the mud creating the future for our culture.

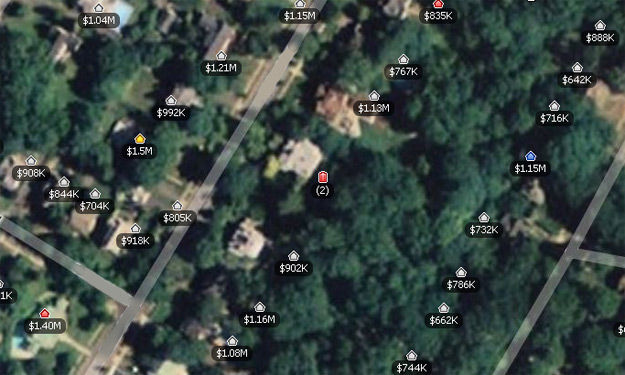

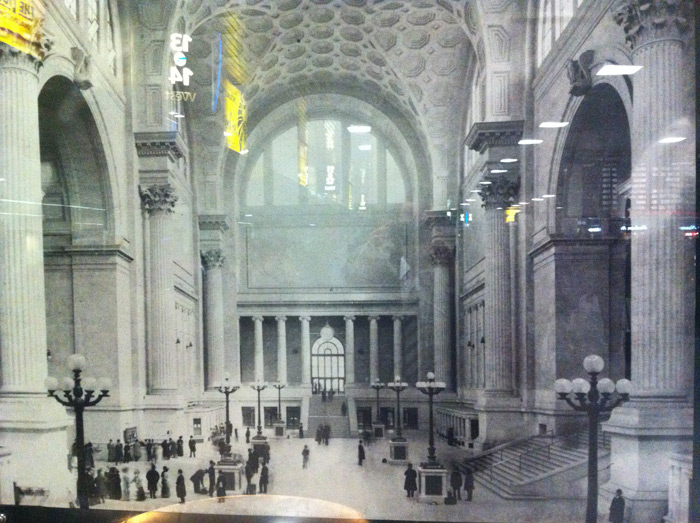

Visionaries elevate us. Here’s a simple representation that I came upon while coming into New York City yesterday:

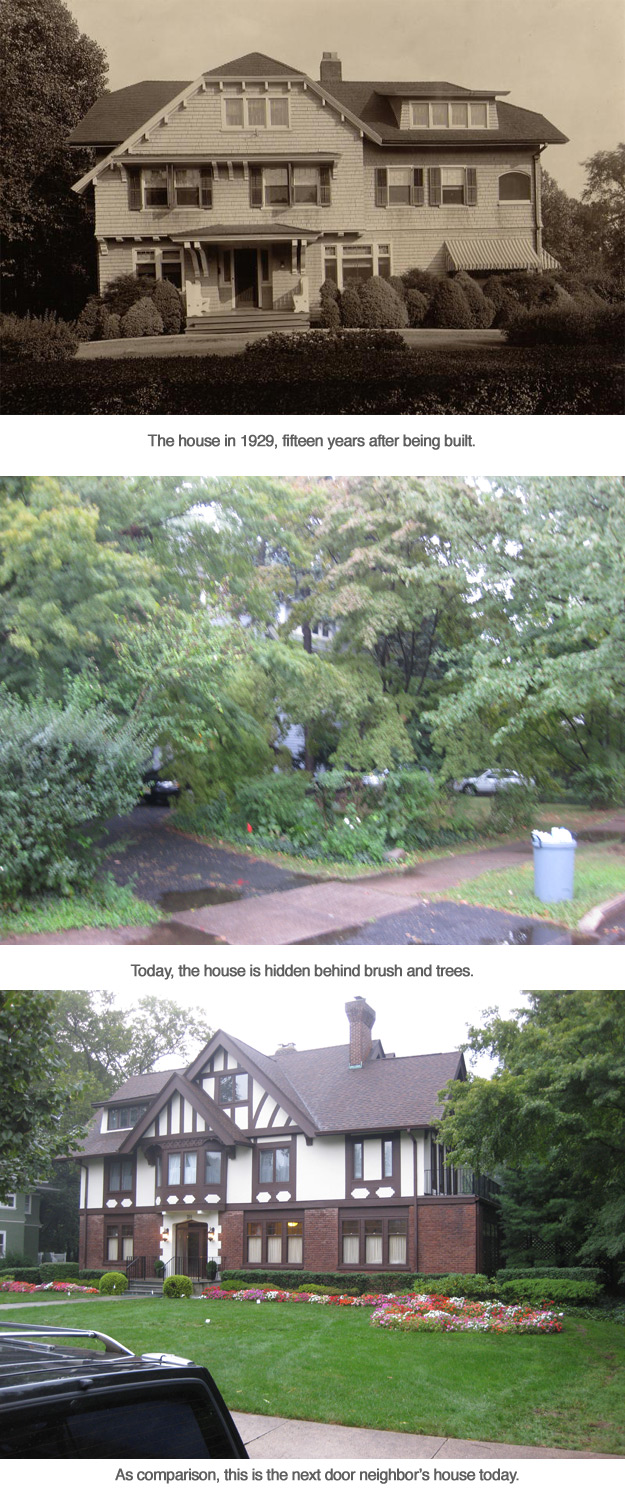

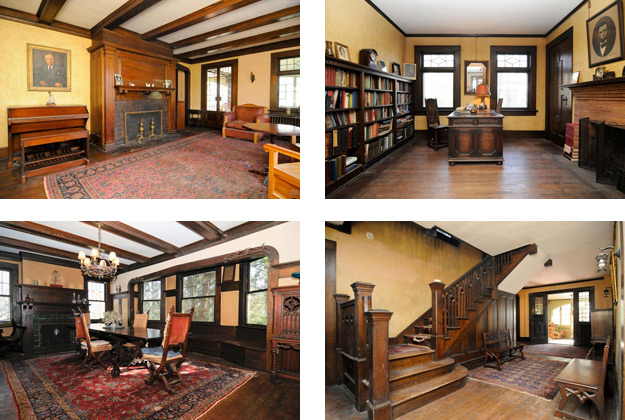

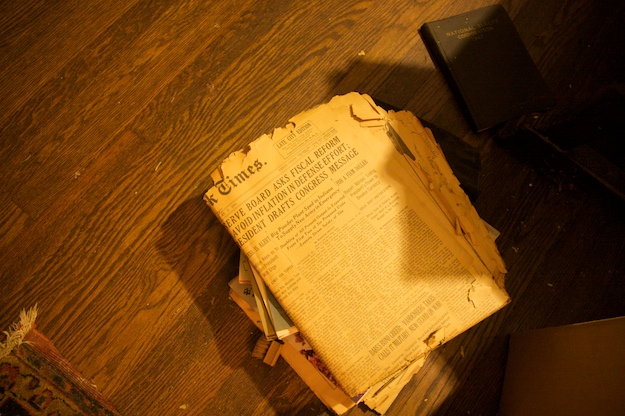

Penn Station, original:

Penn Station, today:

Which elevates us, and which merely manages us?

-Dan