This is part of the Bittersweet Book Launch case study, where Dan Blank and Miranda Beverly-Whittemore share the yearlong process of launching her novel. You can view all posts here.

By Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

Chapter Six: Story World

After all the deep discovery prompted by the previous chapters, this chapter always feels like a sigh of relief. This might just be me, but my novels almost always come attached to a very strong sense of place, and so I have less unpacking to do. But that doesn’t mean this chapter is “easy,” no, there’s still plenty to uncover. Truby wants you to think intentionally about the metaphors and symbols of place you’ll be employing- from seasons, to weather, to the landscape- and the degree to which they have a profound influence on the kind of story you want to tell.

After all the deep discovery prompted by the previous chapters, this chapter always feels like a sigh of relief. This might just be me, but my novels almost always come attached to a very strong sense of place, and so I have less unpacking to do. But that doesn’t mean this chapter is “easy,” no, there’s still plenty to uncover. Truby wants you to think intentionally about the metaphors and symbols of place you’ll be employing- from seasons, to weather, to the landscape- and the degree to which they have a profound influence on the kind of story you want to tell.

In Worksheet Five, you look at much of the work you’ve already done through the lens of your story world. This is the chapter where I usually end up feeling as though things are really falling into place.

Chapter Seven: Symbol Web

This chapter encourages you to use symbols to highlight and amplify the elements you’ve already put together in your book. If I’m being honest, this chapter usually feels the most “gimmicky” to me; perhaps because my first, true love is literary fiction, I find this part of Truby’s approach to be a little too formulaic for my taste. That said, I almost always find something in my own book that I didn’t know was there thanks to this chapter, so what do I know?

This chapter encourages you to use symbols to highlight and amplify the elements you’ve already put together in your book. If I’m being honest, this chapter usually feels the most “gimmicky” to me; perhaps because my first, true love is literary fiction, I find this part of Truby’s approach to be a little too formulaic for my taste. That said, I almost always find something in my own book that I didn’t know was there thanks to this chapter, so what do I know?

Chapter Eight: Plot

Finally! It’s those 22 Story Steps I was telling you about! Lo and behold, all the work you’ve done up until this point dovetails nicely into a strong, well-thought out structure.

That said, this is usually where I branch off from Truby. His method has you sitting down and assigning plot points to each Story Step, but I find that I like to go “backwards;” at this point in the game, given all the work he’s had me do, I already know what’s going to happen in the story. So instead of using a worksheet, I take flashcards and write down each moment or beat, and then, once they’re all down, I makes sure they align with most of the story steps (more on this tomorrow).

Chapter Nine: Scene Weave

My modification of Truby means that I end up with a scene weave just like what Truby ends up wanting you to have, but I come at it differently (I’ll talk more about this tomorrow). Still, it’s awesome to know that if you stick with the system, you’ll end up with a sixty scene outline at this point in the game.

Chapter Ten: Scene Construction and Symphonic Dialogue

This chapter seems very pitched to screenwriters, or for folks who want to hone their dialogue skills. What I need out of Truby is a strong outline, so I find that once I’ve gotten to this chapter, he’s given me what I need.

Chapter Eleven: The Never-Ending Story

Again, I’m usually “out” by this chapter. But he make some good points here- it’s worth looking at.

Tomorrow: The final outline

This post is part of a five part series. Click here for Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four and Part Five.

I’ll begin by saying that were I starting Truby for the first time, I’d go through the book right off the back and type up each worksheet (which he calls “Writing Exercises,” but I like to call worksheets since I’m a nerd). Then I’d “Save As” and rename each worksheet for the book I happen to be working on, since there’s a good chance I’d want to use this method in the future! I keep mine in a favorite notebook so I can reference them once I start writing in earnest (See? There it is- full of ideas I didn’t have before).

I’ll begin by saying that were I starting Truby for the first time, I’d go through the book right off the back and type up each worksheet (which he calls “Writing Exercises,” but I like to call worksheets since I’m a nerd). Then I’d “Save As” and rename each worksheet for the book I happen to be working on, since there’s a good chance I’d want to use this method in the future! I keep mine in a favorite notebook so I can reference them once I start writing in earnest (See? There it is- full of ideas I didn’t have before). Worksheet One, at the end of Chapter Two, is where Truby invites us to state what the book is about. As a literary novelist, this was a radical idea- so much of what I’d learned before I started working with Truby was all about denying that there is such a thing as a single truth of “aboutness” when it comes to writing fiction. There are surely many novelists who write brilliant, perfectly crafted books without thinking about this. But I’ve learned that I’m not one of them!

Worksheet One, at the end of Chapter Two, is where Truby invites us to state what the book is about. As a literary novelist, this was a radical idea- so much of what I’d learned before I started working with Truby was all about denying that there is such a thing as a single truth of “aboutness” when it comes to writing fiction. There are surely many novelists who write brilliant, perfectly crafted books without thinking about this. But I’ve learned that I’m not one of them! Remember those 22 story steps I mentioned back in my first post? Think of the seven story steps you’ll explore in this chapter as the basic building blocks for those 22 steps. This is the chapter where you’ll start thinking more definitively about all that raw material you set down in Worksheet One, and how what you’ve already generated will shape itself into a natural story. Worksheet Two will help you do this, focusing in on your main character’s arc, from their weaknesses and needs at the beginning, to the new equilibrium of the universe at the end. You’ll start to think about aligning your main character’s arc with the arc of the story, so that they’ll be working together, instead of at cross purposes.

Remember those 22 story steps I mentioned back in my first post? Think of the seven story steps you’ll explore in this chapter as the basic building blocks for those 22 steps. This is the chapter where you’ll start thinking more definitively about all that raw material you set down in Worksheet One, and how what you’ve already generated will shape itself into a natural story. Worksheet Two will help you do this, focusing in on your main character’s arc, from their weaknesses and needs at the beginning, to the new equilibrium of the universe at the end. You’ll start to think about aligning your main character’s arc with the arc of the story, so that they’ll be working together, instead of at cross purposes. This is when it starts to get fun! In this chapter and then in Worksheet Three, you’ll get to know your protagonist much better. But you’ll do that by getting to know the other characters in the story too, including the antagonist (in my new novel, there’s more than one protagonist and more than one antagonist, so never fear if you don’t have such a black and white tale- the method can definitely be modified for your uses). You think about the Character Web, and how all the characters in your story can (and must) interact and illuminate each other.

This is when it starts to get fun! In this chapter and then in Worksheet Three, you’ll get to know your protagonist much better. But you’ll do that by getting to know the other characters in the story too, including the antagonist (in my new novel, there’s more than one protagonist and more than one antagonist, so never fear if you don’t have such a black and white tale- the method can definitely be modified for your uses). You think about the Character Web, and how all the characters in your story can (and must) interact and illuminate each other. Truby presupposes that every tale is about a deeper moral system, and that, as he puts it on page 109, “you, as the author, are making a moral argument through what your characters do in the plot.” This is a good reminder that a novel is about many things. But he also loathes propaganda, and argues that only by letting your characters live honestly can your story resonate on deeper levels.

Truby presupposes that every tale is about a deeper moral system, and that, as he puts it on page 109, “you, as the author, are making a moral argument through what your characters do in the plot.” This is a good reminder that a novel is about many things. But he also loathes propaganda, and argues that only by letting your characters live honestly can your story resonate on deeper levels.

You can watch the accompanying video

You can watch the accompanying video  Truby posits that good films (and he gives plenty of convincing examples) include most, if not all, of what he calls the “22 building blocks,” essential elements that keep a story strong. Truby is structured so that if you follow it from chapter one, by the end of it, you’ll have a detailed “scene weave” in hand (see: my trusty cork board), which he describes as “a list of every scene you believe will be in the final story,” based upon these 22 building blocks. Now, screenplays are much shorter than novels, so I adjust this final step to be not so much a concrete scene weave as a detailed description of each moment or beat that I know must happen in the story- but I’ll talk in much more detail about how I modify the end of the book that on Friday. What you need to know for now is that Truby takes you from premise to outline, and holds your hand most of the way.

Truby posits that good films (and he gives plenty of convincing examples) include most, if not all, of what he calls the “22 building blocks,” essential elements that keep a story strong. Truby is structured so that if you follow it from chapter one, by the end of it, you’ll have a detailed “scene weave” in hand (see: my trusty cork board), which he describes as “a list of every scene you believe will be in the final story,” based upon these 22 building blocks. Now, screenplays are much shorter than novels, so I adjust this final step to be not so much a concrete scene weave as a detailed description of each moment or beat that I know must happen in the story- but I’ll talk in much more detail about how I modify the end of the book that on Friday. What you need to know for now is that Truby takes you from premise to outline, and holds your hand most of the way. Each chapter goes into great detail on the subject at hand, and offers up specific sub-elements (I think of them as mile markers that I have to pass within the journey of that particular chapter). At the end of the given chapter, there is a worksheet, which reviews everything that chapter has covered, with plenty of questions and prompts. He fills out each worksheet himself, using a few examples (most often Tootsie– yes, that Tootsie– and The Godfather) which I find to be very helpful when getting a hold of my own work feels murky.

Each chapter goes into great detail on the subject at hand, and offers up specific sub-elements (I think of them as mile markers that I have to pass within the journey of that particular chapter). At the end of the given chapter, there is a worksheet, which reviews everything that chapter has covered, with plenty of questions and prompts. He fills out each worksheet himself, using a few examples (most often Tootsie– yes, that Tootsie– and The Godfather) which I find to be very helpful when getting a hold of my own work feels murky.

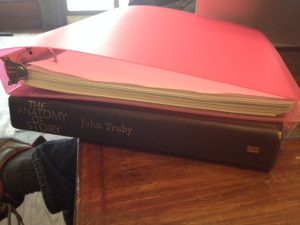

It was my mother who introduced me to John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story (which I’ll mostly call “Truby” from now on, since that’s what my family- my fiction-writing mother, filmmaker sister, and filmmaking brother-in-law, who have all used it too, call it). Truby’s method has served as a major foundation for starting a book ever since my mother introduced the book to me, and so I can’t really remember a time when I didn’t have it to rely on. What I do remember is that the day we bought my copy of Truby, which, as you can see, has been well-loved, I was feeling totally stuck. I had a new idea for a novel but no plan about how to execute it. But when my mother showed me a copy of a book that was supposed to help screenwriters, I remember feeling, well, not insulted exactly, but kind of like, “Wtf am I (a novelist) supposed to do with this?”

It was my mother who introduced me to John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story (which I’ll mostly call “Truby” from now on, since that’s what my family- my fiction-writing mother, filmmaker sister, and filmmaking brother-in-law, who have all used it too, call it). Truby’s method has served as a major foundation for starting a book ever since my mother introduced the book to me, and so I can’t really remember a time when I didn’t have it to rely on. What I do remember is that the day we bought my copy of Truby, which, as you can see, has been well-loved, I was feeling totally stuck. I had a new idea for a novel but no plan about how to execute it. But when my mother showed me a copy of a book that was supposed to help screenwriters, I remember feeling, well, not insulted exactly, but kind of like, “Wtf am I (a novelist) supposed to do with this?”