This is part of the Bittersweet Book Launch case study, where Dan Blank and Miranda Beverly-Whittemore share the yearlong process of launching her novel. You can view all posts here.

By Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

Truby posits that good films (and he gives plenty of convincing examples) include most, if not all, of what he calls the “22 building blocks,” essential elements that keep a story strong. Truby is structured so that if you follow it from chapter one, by the end of it, you’ll have a detailed “scene weave” in hand (see: my trusty cork board), which he describes as “a list of every scene you believe will be in the final story,” based upon these 22 building blocks. Now, screenplays are much shorter than novels, so I adjust this final step to be not so much a concrete scene weave as a detailed description of each moment or beat that I know must happen in the story- but I’ll talk in much more detail about how I modify the end of the book that on Friday. What you need to know for now is that Truby takes you from premise to outline, and holds your hand most of the way.

Truby posits that good films (and he gives plenty of convincing examples) include most, if not all, of what he calls the “22 building blocks,” essential elements that keep a story strong. Truby is structured so that if you follow it from chapter one, by the end of it, you’ll have a detailed “scene weave” in hand (see: my trusty cork board), which he describes as “a list of every scene you believe will be in the final story,” based upon these 22 building blocks. Now, screenplays are much shorter than novels, so I adjust this final step to be not so much a concrete scene weave as a detailed description of each moment or beat that I know must happen in the story- but I’ll talk in much more detail about how I modify the end of the book that on Friday. What you need to know for now is that Truby takes you from premise to outline, and holds your hand most of the way.

Truby is has eleven chapters in it. I’ve found that I use Chapters Two through Eight most faithfully.

Chapter One: Story Space, Story Time (I usually skim this chapter to remind myself how Truby’s mind works, and reorient myself inside the method, but much of what is in it seems rudimentary to me- if you already tell stories for your living, you already live and breathe much of what he says here).

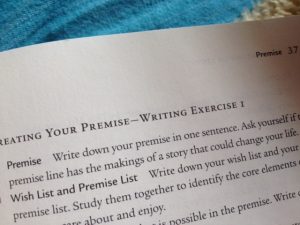

Chapter Two: Premise

Chapter Three: The Seven Key Steps of Story Structure

Chapter Four: Character

Chapter Five: Moral Argument

Chapter Six: Story World

Chapter Seven: Symbol Web

Chapter Eight: Plot

Chapter Nine: Scene Weave (I usually come up with my own method of putting together the scene weave based on the work I’ve already done by this point- I find his way of doing it to be backwards- more on this on Friday).

Chapter Ten: Construction and Symphonic Dialogue (I usually skim this chapter- I find it’s the chapter that’s the most pitched to screenwriters).

Chapter Eleven: The Never-Ending Story (I usually skim this chapter too- it feels more like a recap than part of the method).

Each chapter goes into great detail on the subject at hand, and offers up specific sub-elements (I think of them as mile markers that I have to pass within the journey of that particular chapter). At the end of the given chapter, there is a worksheet, which reviews everything that chapter has covered, with plenty of questions and prompts. He fills out each worksheet himself, using a few examples (most often Tootsie– yes, that Tootsie– and The Godfather) which I find to be very helpful when getting a hold of my own work feels murky.

Each chapter goes into great detail on the subject at hand, and offers up specific sub-elements (I think of them as mile markers that I have to pass within the journey of that particular chapter). At the end of the given chapter, there is a worksheet, which reviews everything that chapter has covered, with plenty of questions and prompts. He fills out each worksheet himself, using a few examples (most often Tootsie– yes, that Tootsie– and The Godfather) which I find to be very helpful when getting a hold of my own work feels murky.

A few notes:

– Don’t be fooled by the word “sheet” in worksheet; I often end up with twenty-five pages for each worksheet! But as I’ll explain tomorrow, all this generated work and research into my project ends up coming in great use as I start to work on the novel, because I’ve already put in so much thought about the characters, the place, the ideas behind the story, etc.

– What I like about accumulating so much work is the fact that Truby has me reiterate and revise and rethink elements over and over again. Premise, for example, is something he asks us to retype and reexamine in nearly every chapter, which means that I almost always end up honing and sharpening what my book is “about,” so that by the time I put together the outline, I have a much better idea about the central conceit of the story than if I’d only thought about it once.

– Finally, I should add that there’s a lot that goes into thinking about a novel long before I use Truby. The book that I’m starting now, for example, is an idea I’ve been scheming about for two years. At one point, I had an outline and about 65 pages, but something wasn’t working (I should have used Truby before I amassed all that work, because I would have discovered pretty quickly what wasn’t working, but I was trying to cut corners, and well, as soon as some folks I really trust read what I had, they pointed out some of the essential flaws in my execution of the idea, and I was back to square one. Lesson learned: use Truby before writing in earnest). I put the book away for a couple months. Once I was ready to think about it in a fresh way, I pulled out Truby, and got back to basics. I already knew, on a gut level, what the novel is about. I knew who the essential characters are. I knew where the book takes place. But even if I didn’t know those things, Truby would have helped me discover them. I’m grateful to be encouraged to slow down and get to know my idea intimately.

Tomorrow: Chapters One through Four.

This post is part of a five part series. Click here for Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four and Part Five.