This is part of the Bittersweet Book Launch case study, where Dan Blank and Miranda Beverly-Whittemore share the yearlong process of launching her novel. You can view all posts here.

By Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

By the time I get to the outline phase in a novel, round about Chapter Eight of Truby or so, I’ve already got a thick notebook of what I’ve discovered by working with him. Here’s what I know:

My premise- what my novel is “about,” specifically what its moral argument is, and how every moment/character in the novel works in consort with that argument

My premise- what my novel is “about,” specifically what its moral argument is, and how every moment/character in the novel works in consort with that argument

My characters- their weaknesses, their desires (what they think they want), their needs (what they need to learn), how they work in connection with all the other characters in the novel, and much more.

My setting- how place and time influences every major moment in the novel

My novel’s basic arc- who is battling whom for what, where they’re doing it, why they’re doing it, and how it’s going to end.

See how much I didn’t know I knew? This is when I feel a little thrill! I didn’t know I knew so much, and I’m chomping at the bit to start writing.

But first I need to make myself a solid outline, using what I know. Because of all I now know, instead of feeling insurmountable, the outline now feels like just one of the necessary steps I must take in writing my novel.

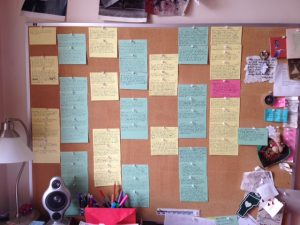

My tools: a big old corkboard, a bunch of notecards (in different colors if you want to sort by character, time frame, or some other way), pens (more than one color if you’d like to sort by character or some other method), and some thumbtacks.

As I mentioned yesterday, in Chapter Eight, Truby encourages us to lay out the 22 story steps and lie our plots over them. But I find this to be backwards; by this point in the game, I already have a pretty strong idea of exactly what the most important moments are going to be (these could be called “beats” as well, because they aren’t exactly scenes; they are the emotional and physical journeys my characters will be taking over the course of the book), and I don’t want to feel constricted by having to see them through the restrictive lens of only being “story steps.”

So I sit down with my big stack of notecards and I start writing these moments down. Simple as that. I number them so I can remember the original order I put them down in, but I’m not afraid to move them around (which is why I do this on notecards and instead of in a single document on my computer). You should note that multiple important moments can (and should) happen in a single scene, e.g. if one of the moments is “character A and character B finally kiss” and another is “character C and character D bond as they spy on character A and B kissing,” those moments will ultimately appear in the same scene, but they are distinct for my purposes because they follow different subplots.

The book I’m outlining right now has two parallel time periods linked by a narrator (who’s a girl in the past and an elderly woman in the present). I assigned green to the present day, and yellow to the past. Each major character in both past and present was also assigned a distinct color (whenever I wrote a character’s name, I wrote it so that when I lay the cards out, I could visually track how important they are, and keep an eye the “holes” (if any) where they seemingly disappear from the plot (which I find often identifies other weaknesses in a plot).

The book I’m outlining right now has two parallel time periods linked by a narrator (who’s a girl in the past and an elderly woman in the present). I assigned green to the present day, and yellow to the past. Each major character in both past and present was also assigned a distinct color (whenever I wrote a character’s name, I wrote it so that when I lay the cards out, I could visually track how important they are, and keep an eye the “holes” (if any) where they seemingly disappear from the plot (which I find often identifies other weaknesses in a plot).

It took me two days of hard thinking to get about thirty scenes of each time period down on the notecards. Then I put each of the green and yellow cards into a rough order. Then I started pinning them up on my empty pinboard, which sits just to the right of my desk.

Now, because this next book weaves back and forth in time, I’ve got an extra challenge in terms of thinking about how to make the plot flow- and this is where the 22 story steps come in handy. Although the book takes place over two different time periods, these two strands of the novel inform and influence each other, revealing truths about the other as the reader pushes on. So although they are distinct from each other, they must be married; I want them to feed each other.

This is where the 22 Story Steps come into help. Once I had the yellows and greens pinned up in a general order, I took Truby’s 22 story steps and penciled them in on top of those moments where they felt relevant.

I stood back and looked at what I had. For the most part, the story flowed! I walked myself through each beat, and realized the story steps really did feed, one into the next, across both time periods, that there weren’t many character holes, that no one seems to be in this story who isn’t vital to it. (That pink card? That’s the moment of revelation for my storyteller, who narrates both time periods, and must learn something as well).

I’m sure there will be parts of this outline that will change. That’s why it’s called an outline- not an immutable straitjacket. That’s why it’s on notecards (although I’ve transcribed what’s on them into a word document in case of apocalypse, I don’t think of that document as an unchangeable thing). What I have now is some help. The bravery to move forward with writing, because I know where I’m going.

Outlining a book isn’t a science. But Truby’s book is the closest I’ve ever come to having, if not a formula, then at least a roadmap, to putting something in place that will help me find my way in the dark room. Truby shines a flashlight on that wild beast who is in the dark with me; the book who is waiting for me to find it.

This post is part of a five part series. Click here for Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four and Part Five.