This is part of the Bittersweet Book Launch case study, where Dan Blank and Miranda Beverly-Whittemore share the yearlong process of launching her novel. You can view all posts here.

By Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

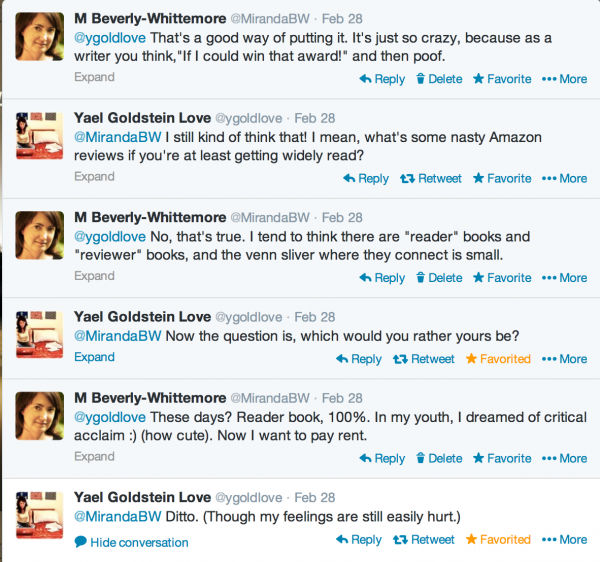

The other day on Twitter, my friend Yael posted about a recent study that found, to quote this article, that “winning a prestigious award not only garners more attention for a book, but also more negative reviews.” Here’s the exchange that article prompted:

What I (usually) like about Twitter is that it goes straight for the jugular. In person I don’t think I would have said out loud: “These days? Reader book, 100%. In my youth I dreamed of critical acclaim.” Not because I’d be embarrassed to admit to that, but because there’s something about 140 characters that can act as a kind of truth serum, and distill beliefs that I didn’t even know I had.

Once I said it, I started thinking about how much writing and publishing Bittersweet is changing my attitude about my career. When I wrote my first two books, I was definitely aware that I was precocious. I was very young, and very driven, and in this culture that often means that someone like who I was then gets serious extra credit. And I did- major book deal, lots of big talk. It was an insidious cycle- because once I’d been given the stamp of approval, I kind of just assumed that people would want to read whatever I wrote, and that meant I believed I deserved the stamp of approval unconditionally.

It’s awful to see it written out so blatantly, but I think now I can finally own up to that assumption.

Yes, I wrote The Effects of Light and Set Me Free because they were surging to get out of me. But I also had a clear belief in the fact that I belonged in the place I’d found myself- in a big-time book contract- and when I didn’t get the critical acclaim (or, let’s be honest, much critical notice at all), I was totally floored/stunned and utterly thrown off balance. I didn’t know who I was as a writer, and part of that was because I’d been driven to write by a striving, hungering need for that next stamp of approval (critical, saleswise) that would make me feel even more accomplished.

The years that came after publishing Set Me Free definitely humbled me and required me to take a step back from the idea that a stamp of approval means much, except in how I choose it to give me meaning.

Two and a half years ago, when I sat down to write Bittersweet, the drive to do so, first and foremost, came because I wanted it to write something readable. Readable- what does that mean? Well, I wanted to create the delicious experience for someone else that I’ve had with a handful of books- the “I can’t put it down, I can’t come to the dinner table, I can’t go to sleep” addictive rush when a book sucks me in. Yes, I had a dream that a book that was that readable would sell to a publisher, and appeal to that publisher to promote- but most of that ambition was in the interest of finding a reader who was like me- of giving her a gift.

Necessarily, I’ve changed my thinking about reviews. Yes, they are necessary, yes, I will read them, yes, some of them will still probably hurt my feelings a bit. But critical acclaim or disdain pales in comparison to that reader out there who says, “I loved this book!” Because she’s who I’m writing for. There were a number of readers who said that to me about The Effects of Light and Set Me Free, and I’m ashamed to admit I didn’t much listen to them, because my sights were set in the wrong direction. But to all those readers who boosted me through my early careers, I say thank you, and I apologize. It’s you I’m writing for. The you who my books have already found, and the you I haven’t met yet.

My premise- what my novel is “about,” specifically what its moral argument is, and how every moment/character in the novel works in consort with that argument

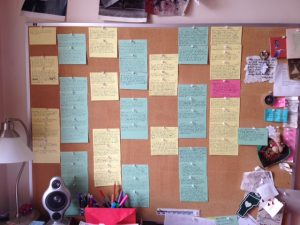

My premise- what my novel is “about,” specifically what its moral argument is, and how every moment/character in the novel works in consort with that argument The book I’m outlining right now has two parallel time periods linked by a narrator (who’s a girl in the past and an elderly woman in the present). I assigned green to the present day, and yellow to the past. Each major character in both past and present was also assigned a distinct color (whenever I wrote a character’s name, I wrote it so that when I lay the cards out, I could visually track how important they are, and keep an eye the “holes” (if any) where they seemingly disappear from the plot (which I find often identifies other weaknesses in a plot).

The book I’m outlining right now has two parallel time periods linked by a narrator (who’s a girl in the past and an elderly woman in the present). I assigned green to the present day, and yellow to the past. Each major character in both past and present was also assigned a distinct color (whenever I wrote a character’s name, I wrote it so that when I lay the cards out, I could visually track how important they are, and keep an eye the “holes” (if any) where they seemingly disappear from the plot (which I find often identifies other weaknesses in a plot). After all the deep discovery prompted by the previous chapters, this chapter always feels like a sigh of relief. This might just be me, but my novels almost always come attached to a very strong sense of place, and so I have less unpacking to do. But that doesn’t mean this chapter is “easy,” no, there’s still plenty to uncover. Truby wants you to think intentionally about the metaphors and symbols of place you’ll be employing- from seasons, to weather, to the landscape- and the degree to which they have a profound influence on the kind of story you want to tell.

After all the deep discovery prompted by the previous chapters, this chapter always feels like a sigh of relief. This might just be me, but my novels almost always come attached to a very strong sense of place, and so I have less unpacking to do. But that doesn’t mean this chapter is “easy,” no, there’s still plenty to uncover. Truby wants you to think intentionally about the metaphors and symbols of place you’ll be employing- from seasons, to weather, to the landscape- and the degree to which they have a profound influence on the kind of story you want to tell. This chapter encourages you to use symbols to highlight and amplify the elements you’ve already put together in your book. If I’m being honest, this chapter usually feels the most “gimmicky” to me; perhaps because my first, true love is literary fiction, I find this part of Truby’s approach to be a little too formulaic for my taste. That said, I almost always find something in my own book that I didn’t know was there thanks to this chapter, so what do I know?

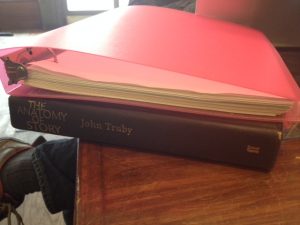

This chapter encourages you to use symbols to highlight and amplify the elements you’ve already put together in your book. If I’m being honest, this chapter usually feels the most “gimmicky” to me; perhaps because my first, true love is literary fiction, I find this part of Truby’s approach to be a little too formulaic for my taste. That said, I almost always find something in my own book that I didn’t know was there thanks to this chapter, so what do I know? I’ll begin by saying that were I starting Truby for the first time, I’d go through the book right off the back and type up each worksheet (which he calls “Writing Exercises,” but I like to call worksheets since I’m a nerd). Then I’d “Save As” and rename each worksheet for the book I happen to be working on, since there’s a good chance I’d want to use this method in the future! I keep mine in a favorite notebook so I can reference them once I start writing in earnest (See? There it is- full of ideas I didn’t have before).

I’ll begin by saying that were I starting Truby for the first time, I’d go through the book right off the back and type up each worksheet (which he calls “Writing Exercises,” but I like to call worksheets since I’m a nerd). Then I’d “Save As” and rename each worksheet for the book I happen to be working on, since there’s a good chance I’d want to use this method in the future! I keep mine in a favorite notebook so I can reference them once I start writing in earnest (See? There it is- full of ideas I didn’t have before). Worksheet One, at the end of Chapter Two, is where Truby invites us to state what the book is about. As a literary novelist, this was a radical idea- so much of what I’d learned before I started working with Truby was all about denying that there is such a thing as a single truth of “aboutness” when it comes to writing fiction. There are surely many novelists who write brilliant, perfectly crafted books without thinking about this. But I’ve learned that I’m not one of them!

Worksheet One, at the end of Chapter Two, is where Truby invites us to state what the book is about. As a literary novelist, this was a radical idea- so much of what I’d learned before I started working with Truby was all about denying that there is such a thing as a single truth of “aboutness” when it comes to writing fiction. There are surely many novelists who write brilliant, perfectly crafted books without thinking about this. But I’ve learned that I’m not one of them! Remember those 22 story steps I mentioned back in my first post? Think of the seven story steps you’ll explore in this chapter as the basic building blocks for those 22 steps. This is the chapter where you’ll start thinking more definitively about all that raw material you set down in Worksheet One, and how what you’ve already generated will shape itself into a natural story. Worksheet Two will help you do this, focusing in on your main character’s arc, from their weaknesses and needs at the beginning, to the new equilibrium of the universe at the end. You’ll start to think about aligning your main character’s arc with the arc of the story, so that they’ll be working together, instead of at cross purposes.

Remember those 22 story steps I mentioned back in my first post? Think of the seven story steps you’ll explore in this chapter as the basic building blocks for those 22 steps. This is the chapter where you’ll start thinking more definitively about all that raw material you set down in Worksheet One, and how what you’ve already generated will shape itself into a natural story. Worksheet Two will help you do this, focusing in on your main character’s arc, from their weaknesses and needs at the beginning, to the new equilibrium of the universe at the end. You’ll start to think about aligning your main character’s arc with the arc of the story, so that they’ll be working together, instead of at cross purposes. This is when it starts to get fun! In this chapter and then in Worksheet Three, you’ll get to know your protagonist much better. But you’ll do that by getting to know the other characters in the story too, including the antagonist (in my new novel, there’s more than one protagonist and more than one antagonist, so never fear if you don’t have such a black and white tale- the method can definitely be modified for your uses). You think about the Character Web, and how all the characters in your story can (and must) interact and illuminate each other.

This is when it starts to get fun! In this chapter and then in Worksheet Three, you’ll get to know your protagonist much better. But you’ll do that by getting to know the other characters in the story too, including the antagonist (in my new novel, there’s more than one protagonist and more than one antagonist, so never fear if you don’t have such a black and white tale- the method can definitely be modified for your uses). You think about the Character Web, and how all the characters in your story can (and must) interact and illuminate each other. Truby presupposes that every tale is about a deeper moral system, and that, as he puts it on page 109, “you, as the author, are making a moral argument through what your characters do in the plot.” This is a good reminder that a novel is about many things. But he also loathes propaganda, and argues that only by letting your characters live honestly can your story resonate on deeper levels.

Truby presupposes that every tale is about a deeper moral system, and that, as he puts it on page 109, “you, as the author, are making a moral argument through what your characters do in the plot.” This is a good reminder that a novel is about many things. But he also loathes propaganda, and argues that only by letting your characters live honestly can your story resonate on deeper levels.

You can watch the accompanying video

You can watch the accompanying video