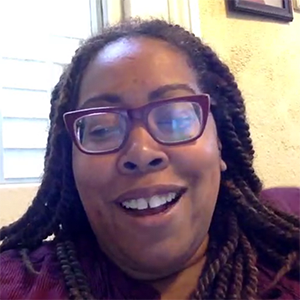

Today I am excited to share my interview with sound artist Margaret Noble. I am inspired by Margaret’s habits as a creative professional, especially the intentional choices she makes to improve her craft, grow as an artist, and ensure she makes time to create.

Some of what we cover in our chat:

Some of what we cover in our chat:

- How she views marketing and communicating about her work as integral to improving her craft, not just as “marketing” to generate more business.

- How she moved across disciplines from dance, to DJing, to art.

- The personal situations that sparked pursuit of her own artistic craft.

- How she chooses art over money.

- Her experience in collaborating with others.

- The value of teaching in improving her craft.

- How she navigates through rejection and anxiety.

- How she organizes her life to ensure she has time for art.

Click ‘play’ above to listen to the podcast, or subscribe on iTunes, or download the MP3.

About Margaret

Margaret Noble is a sound artist whose work resides at the intersection of sound, sculpture, installation and performance. She holds a BA in philosophy from the University of California, San Diego and an MFA in sound art from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Her projects have been featured on KPBS and PRI and reviewed in art ltd. magazine, Wired magazine, San Diego Union Tribune and the San Francisco Weekly. She has been awarded the International Governor’s Grant, the Hayward Prize and the Creative Catalyst Fellowship. Her artistic residencies include the MAK Museum in Vienna and the Salzburg Academy of Fine Art. She has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego and at the Ohrenhoch der Geräuschladen Sound Gallery in Berlin. In 2014, she won first place in the Musicworks magazine electronic music composition competition.

Here are some excerpts from our chat:

How Her Sound Art Career Began With Dance

“We can take it back to the 1980s hip hop culture. I grew up in an urban environment where the greatest things on earth were sounds. Maybe you didn’t have a beautiful home or beautiful street or any money in your pocket, but you could always have a good time with music. Cars would be driving around bursting with sounds, human beat boxing, rapping, all these amazing sounds were around me when I was a little kid. My initial interest was dance, I did it for years.”

I asked about when she began dancing:

“As a skinny awkward child, probably eight, at the rec center. Just street dancing, or thinking you are doing street dancing. I probably wasn’t doing it very well. That was everything to our neighborhood. That’s all we did: kid shows, talent shows, and making dance routines all the time.”

“You definitely had to have a level of bravado, and I wasn’t the one spinning on my back, I was in the background wanting to do that. It was intimidating. Sometimes it was at the rec center, but sometimes it was in the middle of the park. They are doing dance-offs. It was amazing and exciting, you forgot where you were.”

I asked her about how she practiced the craft of dance:

“It was me and my friends alone for years. I didn’t have the moves at that age, but eventually you get the courage to submit a dance routine to the talent show. Maybe it was that moment that kept pushing me to submit performances and auditioning. It was 4th grade, we are on stage, dancing to ‘Fame’ with friends. It probably wasn’t that great, but it took courage.”

“In high school, I was on the dance team, then in college I got a dance scholarship and I took traditional dancing. My big high school thing was that I got to dance in the Super Bowl pre-game show, so I got to learn stage dancing too.”

“It was just after high school that I learned about underground raves. All of the sudden, you get a map to go to a secret location and dance all night long. I would chase DJs around. I danced at these free-form events. It’s not restricted to any code, because it’s rave dancing. It’s still beat-focused, but substantially faster. There is a performance there as well, but it’s different because it is a collective performance.”

I asked her how she found her place in this culture, which tends to take place in dark rooms with hundreds of other people. Her response:

“It’s really about finding the DJ who played the sounds you wanted to hear. There’s about 40 subdivisions of house music, so you found your place by finding the person who weaved the sounds that you wanted to hear. That was the chase, that was the unity.”

How the End of Her Marriage Sparked the Beginning of Her DJ Career

I asked about her decision to make the jump from consumer to creator:

“There’s two things pivotal in that decision. One is that I wasn’t finding what I wanted to hear; there were certain characters of sound that I wanted; drum patterns, shuffling beats, thick bass lines; continuous mixing. So I wasn’t getting that, and I needed it to dance.”

“The other thing was — and this is personal — but it was the same night that I knew my first marriage was over, that I knew I needed to buy turntables. I literally laid awake on my bed, saying, ‘I know my husband is not coming home tonight, I guess that means my marriage is over. I think I should buy turntables.’ It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me. I mean, divorce sucks of course, but I’m here now because of that decision.”

“I think the sound art is an extension of DJing. I’m grateful that that creative outlet came to me. It saved me.”

From Listener to Creator

“I realized that if you really want to control the grooves, that you should probably get behind the decks.”

Okay, so this point is huge to me. That moment when someone is enjoying being a part of an experience and community at a rave, and deciding that they want to take a leap to the next level: to controlling the music itself.

“I switched from chasing other people’s sounds, into learning to cultivate my own.”

“My particular interest was Chicago house music. So I bought two turntables, then I moved to Chicago.”

Developing Her Craft

I asked how she developed her craft of DJing:

“I was terrible at first. TERRIBLE. I don’t know if you know what a ‘train wreck’ is, but if you are on the dance floor, you do not want to hear the mixes, and the beats need to be continuous. This is house music specific: if you do a bad job of mixing and you don’t sync the beats up, you are messing with people’s dance, you are messing with people’s vibe. It took me a long time. I had to work really hard to nail that skill.”

“My first year or two, I remember that I was doing my bachelors at USD in philosophy and all I want to do is run home and practice. I finally learned that I would improve if I could record and listen. It’s very hard to know if you are doing well when you are actually playing. You are in that space of experiencing it, but you are not able to critically listen. Recording is what really transformed it.”

“At first I got gigs prematurely because I was the girl DJ. They were like ‘Oh cool! Girl DJ, we never had a Girl DJ!’ And I wanted to capitalize on that, but I wasn’t always ready. I can remember in San Diego, it was a really great gig. I got up on the decks, and I was definitely not feeling comfortable in the technical situation. Everyone was like, ‘Yes! House music! She’s gonna kill it!’ Then I got up and I sucked. I sucked. I cleared the floor. It was so heartbreaking. I knew I had to stop and practice more. I learned so much from that experience, and I’ll be damned if I ever screw up like that again.”

She then moved to Chicago specifically because of “Chicago house music,” which is where the DJs she loved were from.

I asked if she was able to DJ full-time, if this was paying the rent. Her response:

“No, no. I’ve always carried myself by bartending or waiting tables. I learned at 18, that if you wanted to live and have time, that bartending or waiting tables is the way to go because you only have to do a couple shifts, and you can make enough money to really live. That was always the income source that supported my art habits. Until now, I do it by teaching.”

Transition to New Inspirations

“I submitted demos and submitted demos until I finally started getting gigs. I got a DJ agent, and just pushed pushed pushed. It was really exciting, but eventually, there was a creative stagnation, because you can really only do so much with two pre-pressed records. I don’t know if I was inspired anymore by just trying to make a dance floor move. I wanted to grow.”

She went back to school and got her MFA in sound art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in her early thirties.

On Collaborating with Others

“That’s how I broke into the art world: finding people with visual media who needed sound to support or augment the performance. I didn’t want to be sound designer for hire. I tried it and hated it. I wanted to have a voice.”

“Collaboration is exhausting. I’m a control freak too, so a lot of my friends who are extraordinarily talented are not as organized as me. That makes me crazy. The actual day-to-day management of projects is difficult. Then, when you make something beautiful, you forget how painful it was to get there, and you celebrate. You have to negotiate, give and take, and that is really challenging.”

Choosing Art and Voice, Over Money

“I think if I wanted money, my life would be very different. Experience is so much more rich and fulfilling than a pocket full of cash without being proud of my work.”

“I tested doing sound design for theater; hated it. I considered moving to LA to get an editing job, for dialogue editing; pulled out of that one. I was never in this to be a gun for hire. I’ve always been in this to have a voice. To keep the integrity of my work, if that means I will not be able to support myself from my art, then I would just keep it this way and be proud of putting out things I believe in. Rather than getting money, and cheapening my experience.”

Art and Teaching

“I’m in my eighth year of teaching; the more I experience this, the more I realize that these are necessary companion projects [art and teaching]. To articulate is to further your art practice. To deal with other artists and learn about their vision, is to further your art. The reality is that you have a responsibly to support the arts, and education is a great way to do it. I’m finding ways to make it one career, instead of two separate careers: teaching and the making of art.”

“Thinking of art not as a career, but a lifestyle.”

“I work at a charter school that serves the entire city of San Diego. It’s a project-based learning school, which means absorbing your content through doing, as opposed to more traditional textbook models. I’m the digital art instructor. I basically do whatever I like because there are no standards for digital art, no test I need to teach to. I work with twelfth graders doing an art and technology project.”

Her enthusiasm in describing this job was off the charts. She listed out what she does:

- “I can push it as far as I want, I can curate it, I collaborate with them.”

- “I push them to produce their best possible work.”

- “I learn so much from the work they make.”

- “I’m forced to learn new skills in order to teach them.”

“After I graduated art school, I said I’m not going to wait tables anymore, and I bought a van. I drove around the country, lived off a savings account, and just experienced things, and just applied for opportunities, hoping something would come through. I actually did get a fully-funded, two-month residency in Salzberg, Austria. I’m there, running out of money. I applied on Craigslist to anything remotely related to my interests. That is when I considered the dialogue editing job in LA. But then High Tech High had an ad saying they wanted a multimedia instructor, and I had an interview over the phone, and the rest is history.”

“I just had to quit waiting tables, it was like a nightmare. It was haunting me. I did it for 13 years. I was sick of smiling for money, of doing service for money. I was sick of that kind of transaction where my relationship with you is about pulling money from you. I stashed as much cash as I could, I outfitted a van.”

When I expressed how impressive it is that she did what many people dream to do — take a break from a career that no longer feels inspiring in order to find that next version of herself — she responded:

“I can’t believe I did it. I made my cat come with me, too.”

Steeped in Rejection

When we chatted via email prior to the interview, she mentioned this, “My career management is steeped deeply in rejection. I apply to hundreds of calls for work per year and 90% say no. That is rejection, that is painful and if I didn’t do this then my work would never move outside of the city I live in. But it hurts and I know many artists who won’t go through this because the rejection stings too much. But, I have learned a lot by these trials, including the fact that the rejection doesn’t always mean your work isn’t good.”

She continues in our chat:

“In the beginning I was really naive, and picked things that were obviously way out of my reach. I was like it’s a numbers game, I’ll just send it out there. So at first, it was really unsuccessful.”

“I mean, what is the alternative? Doing nothing? Sitting in your home not getting your work out there? What is the point then? So I think my skin just got thicker. But then I learned to be more strategic, vetting the opportunities before I apply. I try to get as many applications out there, because then I have a better chance of someone saying yes, right? If ten say no, and one says yes, that means I have another opportunity to show my work. Forget about those other ten.”

“I can’t live on the local opportunities, I need to see if my work reads beyond those who know me. To see if strangers will accept your work. Those who don’t have any emotional obligation to pick up your work.”

“I’m fine with the rejection now. People say yes every year, so there is enough people saying yes, to make the other ones not hurt as much.”

Organizing Her Life to Create

“I’m very regimented. I’m a planner. I refuse to think about school after I leave. I take a chunk of time before school starts, and plan the entire semester out so I don’t have to think about it at night. I walk in, I look at my plans, and I go with those kids as far as I can. Of course I adjust along the way, but I have a strong enough template that, even though it’s spring break, I’m not thinking about them at all, even though we have critical due dates coming up, because I have this plan that I trust in.”

“If you don’t plan, then every night is spent thinking, ‘well what do I have to do tomorrow?’ If I have to do that, then I’m not going to be making any [creative] work at all.”

“The struggle is when I first get home, that is when I want to take a nap, right? And I have to feed the cats, and my house is a mess. So I give myself an hour of transition mode, where I can just take care of my home. I actually think that is part of my practice. Just taking care of my life makes me a better artist.”

“Then I brew some coffee and try to do a task. I usually have goals, and every night I think about what I achieved today.”

Then Margaret said something that I can’t understate the importance of:

“Embedded in all those structures, I have a solid 2-3 date nights with my husband per week.”

That she SCHEDULES aspects of what I would define as both ‘relationship management,’ and ‘mental health.’ She doesn’t wait for there to be a break in her schedule to take time with her husband, they schedule it.

It gets better — and this to was a huge insight to hear from her:

“That is what keeps me going, and I pretty much blow off all other [responsibilities]. I haven’t been to a work happy hour in five years. I have managed everyone’s expectations that I’m not coming to happy hour. I have other things that I have to do. My friends too, they are like, ‘Margaret, you are so lame.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m really sorry, but I really have these things that I can’t let go of.’ So I’m trying to manage their expectations too.”

The Risk (and Anxiety) of Working Experimentally

She went on to mention other risks that she takes: “The idea of working experimentally, in the classroom and in the home, is a risk to me, because I don’t know the outcomes of the projects, and I don’t know if they are going to succeed. But maybe the risk is what makes it interesting. That there is a lot more fun when there is a risk, than if it’s safe. There’s growth right? Art should never stagnate. Maybe the risk is why we are doing it.”

What fascinates me is establishing a process to be uncomfortable in the unknown. To push oneself from is known, and therefore feels safe, into what is unknown, and may not work out.

“Don’t get me wrong, I have anxiety. I will worry worry worry. I have to watch how much caffeine I drink, I quit sugar, I use a lot of strategies [to manage anxiety], because I take so many risks, I put myself out there so much. It’s a peaks and valleys experience.”

Training People to Understand Her Art

We are a physically-oriented culture, and yet, Margaret’s art is invisible. I asked her about her experience in getting people to even understand her work as art. Her response:

“Ultimately it’s like painting, except you can hear it instead of see it. It’s more focused on the experience of sound, and less focused on the musical composition. Just to think about sound purely in its own form. It is an impossible thing to explain, because there is a tension between what sound art is, and music. We are a visually-centric world. It’s not even within people’s grasp to envision art beyond a visual capacity. I have to do a lot of contextualizing to help them get close to it. It’s also confusing because it usually comes with a visual component too. Sometimes people need to focus on the visual component to even understand the sound.”

“There is fine line between experimental music and sound art. Some would say that sound art is musical. It’s an unconventional treatment of audio, and it’s mixed in with other media. It might be used at a dance recital, at a puppet show, used in support of a film. Recently, I have been using sound with objects, to animate them. So there will be a recording device hidden within them. It is like the hidden medium, but you need physical forms for it to travel.”

Thank you to Margaret for making the time to meet with me. You can find her online at:

For more interviews and behind-the-scenes stuff on my book Dabblers vs. Doers, click here.

Thank you!

-Dan

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Topics we cover:

Topics we cover: