Today I am thrilled to share my interview with Jeremy Chernick, a special effects designer for Broadway productions, Cirque du Soleil projects, museum installations, music videos, TV, and film. Basically, Jeremy makes it snow, rain, burn, bleed and explode on stage. He has worked with J&M Special Effects since 2006.

This interview is part of the research for a book I am writing called Dabblers vs. Doers, which is about working through RISK as you develop your craft and build a meaningful body of work. For Jeremy, his risk is not just personal, but highly collaborative; it’s his job to ask actors, an audience, and theater producers to be comfortable a few feet from small explosions.

In our discussion, we cover:

- Breaking big creative risks down into manageable moments.

- How lots of bad ideas are a part of the creative process.

- The value of communication, and the agreement you make with your audience.

- The pressure of creating the spectacular.

- The part of the creative process that no one wants.

- His creative career journey.

- How his professional life affects his personal life, now that he is a father.

Click ‘play’ above to listen to the podcast, or subscribe on iTunes, or download the MP3.

This was one of those interviews where me traveling to interview Jeremy in-person had a profound effect on my understanding of his work. I was able to meet his colleagues, see the workstations where they create effects, see their stock of gadgets and raw materials that they purchase from vendors. I was also able to overhear conversations between colleagues of his, like:

- “What are we supposed to be doing with this machine gun over here?” Later on, while Jeremy and I were chatting, I could hear a machine gun being fired in the background — a prop gun shooting blanks, but the sound and feeling of a machine gun nonetheless. Not the usual thing you hear in a workplace.

- Another discussion when someone hung up the phone after a discussion about a production that was asking for an incredible amount of water to be brought into a stage setting. The staff broke this request down into what was reasonable, and where challenges would come up with compliance with the building owner, etc. To these people, a request to deliver and manage thousands of gallons of water in an artistic production was perfectly normal.

Again and again in this interview, the topic of effective communication came up. I have to say, this jumped out at me from my very first experiences with Jeremy. He is clearly very busy, yet responded to my emails very quickly and efficiently. He also was accessible — we met the week after I initially reached out to him.

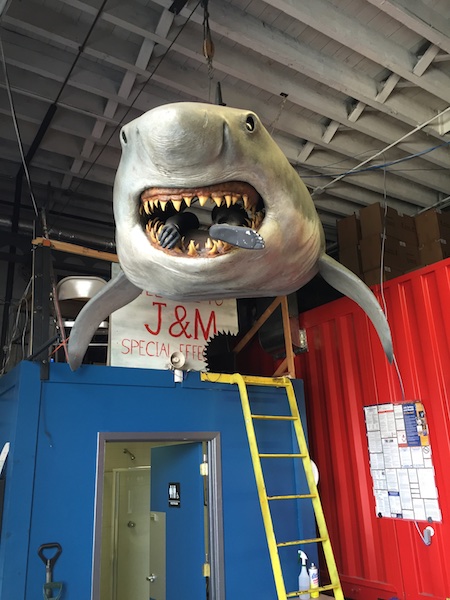

Here is a tour of my visit with Jeremy at J&M Special Effects, which is situated on the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn:

When you first walk in the door, you’re greeted by a life-sized shark:

Jeremy and I:

He took me into a special padlocked room full of prop guns for use as special effects in productions:

A workstation where they create special effects:

There was a lot of equipment throughout the facility. Need wind? They’ve got that covered:

Bathroom reading at a special effects shop: Welder’s Handbook:

Here are some excerpts from our chat:

BREAKING BIGGER CREATIVE RISKS DOWN INTO PRECISE (MANAGEABLE) MOMENTS

“Nowadays, I get asked to do the hard things. I tend to do a lot of ‘tricks’ or moments in a show that are more complicated or take a lot of specific thought, as opposed to something that gets blocked quickly during rehearsal.”

He gave me an example from the Manhattan Class Company production of Punk Rock, directed by Trip Cullman. It’s a dark show about private school kids in London, where a massacre occurs at the end.

“It’s gunshots and… blood delivery gadgets, and how they’re incorporated into the actors, the actors’ movement, but also into the scenery, the props, where they were hidden.”

“[The director] will describe his dream scene to me, and then I will try to dissect it in a way that breaks it down into very precise and tiny moments. So a story that takes one second on stage, I may break out into three or four things that are happening simultaneously, and how those are blocked. In that case, there are multiple risks. So the risks to me are, firstly, safety for everyone involved, including the audience. Secondly, it not selling, and the story not being told. That’s a big risk: does what I think in my mind and what the director thinks in their mind, and the actors all come together to make a moment that really does tell the story, or is it lost? Lastly, getting everyone to do it, and it all to work.”

LOTS OF BAD IDEAS ARE PART OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

“I say a lot that some of the ideas that I have, the rough early stages of planning will be filled with terrible ideas. Hopefully we will find the good ones, and cast away the terrible ideas. That is part of my process. I come to a moment in a show, and I have to think about it and think about it, and I come up with ten ways to do it, then it slowly boils down to the ways that I feel more confident in.”

I asked him about moments of a creative impasse, where none of the ideas are working. He responded:

“Under the [best] case scenarios, I hope to learn that way before the actors are involved. I am lucky and have access to a big play space. We are sitting in it in Brooklyn on the Gowanus Canal, where I can mockup a lot of the ideas that I have, and quickly learn how they work. Just because on a piece of paper and in my mind — this leads to that, and it’s all a plumbing moment, will then spurt a giant disgusting blob of blood on the wall, that will seem as if it came out of the back of someone’s head, when they are unfortunately shot — I can set that up here in a very jerry-rigged way, and see whether it is believable, see the problems that it might have.”

THE AGREEMENT WITH YOUR AUDIENCE

“How I trick the audience, or in better terms, how I try and convince the audience to play along, to agree with me that we are telling a story and they are going to stay with the story. That is an agreement that we make as audience members with the people on stage.”

So much of what Jeremy told me was about communication. In a scene where he had to stage the convincing moment where someone on stage shoots themselves in the head, he mentioned that the prop was a rubber gun. I asked why, and he explained how a switch would take place: first the actor would show the audience a working prop gun that had action. This is part of convincing the audience that it is a real gun. Then a subtle switch would happen and the actor would be using a rubber gun for the scene where they actually shoot themselves. The rubber is a way to communicate to the actor that this gun is 100% safe. There are no mechanisms in this object that could possibly hurt you when you place it near your head. Again and again, Jeremy brought up safety concerns as the first answer when addressing a scenario. But this nonverbal communication via a rubber gun was striking to me.

In describing this single moment in a show, he described the complicated dance between the actor, the stage manager, and an effects person.

“Everyone knows that he didn’t just shoot himself in the head, everyone knows that it’s not his brains and blood on the wall. We all know these things, but we have to believe, or else the play doesn’t really work. A magician friend of mine, Matthew Holtzclaw, said magic is an agreement between the magician and the audience. The magician says, ‘I’m going to trick you,’ the audience says, ‘You are going to trick me,’ and then you go about the process of doing that. The goal of the magician is to trick you, and for you to say, ‘I was tricked, I have no idea how you did that.'”

THE PRESSURE OF CREATING THE SPECTACULAR

When he told a story about the work he did on Aladdin the musical, we talked about the scale of the production, and the collaborators involved: “Designers of every kind — there is a magic consultant, a fight choreographer, a video designer, lighting, sound, costume, directors, choreographer and producers, and the fantastic Disney mechanism on top of all of that.” I loved this quote about a production of this scope, with these partners:

“They are willing to accommodate what is necessary to do the spectacular.”

He described it as both, “… a wonderful environment to play in, as well as full of unbelievable pressure.” A moment later after he described how he helped create the effect of the genie coming out of the lamp for Aladdin, he concluded that it was a collaborative process that is “a pure joy, but also terrifying.”

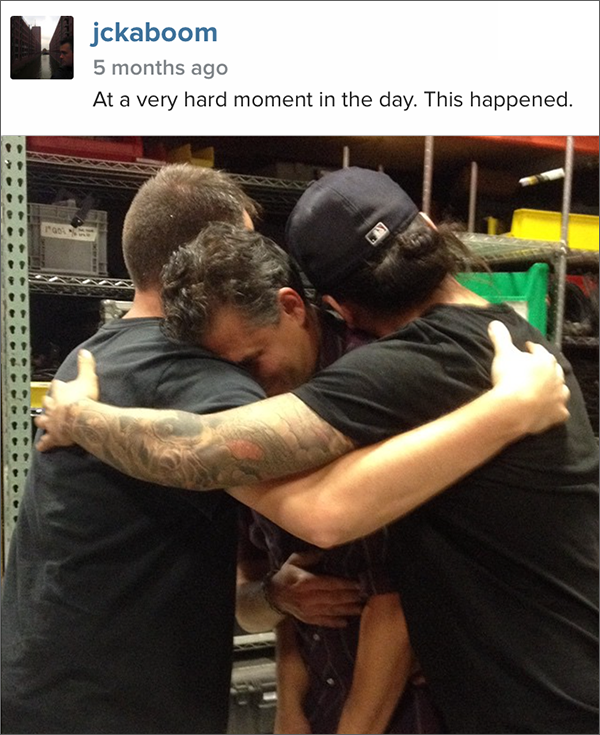

I saw this photo on Jeremy’s Instagram feed, which gave me indication of the emotional complexity of his work:

THE PART OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS THAT NO ONE WANTS

“Inevitably, the most nerve-racking and stress-inducing portions of my job are always communication-based.”

“I take a lot of responsibility, and I find that to be more stressful than delivering the effect. I am the great apologizer, and that is the number one portion of the job that is terrible and that no one else wants. Whatever the problem is, and even if I had nothing to do directly with the problem, I’m responsible and I tend to take that ownership. All of these things, especially in theaters, are all carried out by stagehands, by stage managers, by actors. If there is a problem, I tend to come in and take responsibility to protect those people because they are doing an amazing thing that I forced them to do. That portion of it is much more stressful – the 10 p.m. email from a stage manage that they had a problem; that an actor is nervous or a cue didn’t happen. Not safety related problems, but more that something isn’t happening the way they want it to.”

When I asked him about having undergraduate and graduate degrees in communication (Queens College, 1990-1994, bachelor’s degree in communications, and University of Illinois at Chicago, 1995-1997, masters in communications), he seemed to explain it away as an accident. But clearly it ties into every aspect of what he does. He is a great communicator, and that is critically necessary to such a collaborative process, one that involves convincing the audience of a special effect, and of course, of providing the utmost safety to all involved.

HIS CREATIVE CAREER JOURNEY

When I asked Jeremy how he got into this field, he didn’t describe some kind of obvious path. He wasn’t a pyromaniac as a kid, he wasn’t blowing stuff up in his garage. He actually described that part of his job – the explosive part — as “I don’t really enjoy it.” So this wasn’t some dream job of a kid who was obsessed with firecrackers.

He told me that he had a learning disability, and was taken out of his local high school to go to a high school with a program to help him work through that. His assessment of those years is, “My whole high school experience was about figuring out that I’m not dumb.”

He had no background in theater either. He only took an acting class in college because he thought it would be an easy A. As he continued taking courses, he described the process as “I thought I was an actor, I thought I was an electrician, I thought I was a carpenter — I was terrible at many of those things, if not all of them.”

He chose to take jobs backstage in theater instead of waiting tables for normal everyday reasons: it was more fun and gave him a social scene to be a part of. At the time, he was in Chicago for graduate school, and described what he learned from productions there. They were able to take bigger risks than what he felt New York productions could. “The craziest of theater” is how he described it. He tried acting, stage managing, hanging lights, and other jobs in theater.

He and two friends (one of whom later became his wife, Anna Catherine Rutledge) then took a road trip around the country to try and launch their own theater. When I asked about their plan, he described that they were 20, had no plan, and just went to these cities and hung out and see if any of them felt right.

But none of the towns on their planned itinerary felt right (Boulder, Los Angeles, Portland, among others). He said, “We traveled the whole country and pretty much gave up.” On their way back, they stopped in Austin, Texas, simply to visit a friend. They were going to stay a single night, but found that they had too much fun. Days later, they reflected on how much fun they had in Austin and that even though they hadn’t previously considered Austin, it was perfect for their theater idea.

They moved to Austin and created a theater company called The Fabulous and Ridiculous Theatre. I wish I had more time with Jeremy to explore this phase of his life, and am thankful for the reporting from The Austin Chronicle which provides detailed background of this theater in this article, as well as reviews of productions in their archives.

I can imagine someone asking Jeremy, “How can I get into special effects for famous Broadway productions?” and him answering, “Go to Austin and start a theater with the acronym F.A.R.T.” (Yes, he and his friend were well aware of the acronym when they chose the name.)

Which is the point of why I love exploring Jeremy’s career path. His was not a manifest destiny of a theater-loving child. It was full of risks, setbacks, and a circuitous path around the country.

The latter part of our conversation goes into detail about his career path. You’ll hear how Jeremy took risks, and in doing so, lucked into moments that developed relationships and skills that eventually led him to his current career.

His big break in special effects came from a colleague who made a special request. Jeremy tackled the problem for his friend, and said, “I learned much later that there were a lot of big fancy professionals in the world who wanted that job, but I was the guy from next door who solved problems.”

We ended the conversation discussing how his personal life effects his professional life, and how he manages things differently now that he is a father.

Thank you to Jeremy for making the time to meet with me. You can find him online at:

For more interviews and behind-the-scenes stuff on my book Dabblers vs. Doers, click here.

Thank you!

-Dan

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS