Today I want to talk about a part of my work that I rarely discuss: the consulting I do with organizations outside of publishing. Over the years, I have become convinced that I can better serve writers if I understand more broadly what works in terms of sharing stories and engaging a community beyond the context of books.

How can educational institutions better connect with the communities they serve? And what can writers and creative entrepreneurs learn from that? These are questions I have been considering through work I have been doing for three organizations – all three of whom are focused on EDUCATION, not publishing. I have had the pleasure of doing work with these fine folks so far in 2014:

- PS 123, a public school in Harlem, NY

- Sesame Workshop, a non-profit who is behind Sesame Street

- Knowledge Universe, a private company focused on early childhood education, most prominently through their KinderCare centers.

Since a lot of my work is private and even proprietary to these organizations, I won’t go into too much detail about each organization. Rather, I will share insights as to what I feel writers and creative professionals can learn from the type of work I do with these and other organization.

Three big things to discuss:

ALL PROCESSES ARE HUMAN PROCESSES

Too often, people ask for “best practices” or a strategy, ignoring the most important element of what it means to share a story and engage a community: PEOPLE. So, for an author, this could be a marking plan or book launch strategy. For an organization, it can be how they craft content that engages their ideal audience in a meaningful way, and leads to larger goals around growth or revenue.

How often in your career have you seen a company you work for or with spend loads of time and resources crafting this perfect plan for growth, only to fail in adequately:

- Providing the human resources needed to support it.

- Communicating that plan to the correct people within the organization and train them on how to integrate this plan with their other responsibilities.

- Understanding the needs and goals of their partners in the process – so you hit stumbling blocks before you even reach your audience.

- Consider the behaviors of the folks they intend to reach. Perhaps this was a failure to consider where they are, or maybe it was misjudgment in terms of the messaging that would engage them.

In my career I have seen the behind the scenes process of organizations relaunching website fail again and again. In some cases, these were year-long projects costing (and I’m not kidding) more than a million dollars, and thousands of hours of employee time to create. And regardless of this resource expenditure, the website failed to meet basic needs of their ideal audience.

Of course, I have seen this happen with individuals as well – folks who spend six months designing their “perfect” author website, only to feel a profound sense of confusion when it does zero to connect with readers.

What is often missing from this process is involving the ideal audience early in this process, and at every step of the journey. By the time the strategy, plan, or even website launches, you should have a clear sense as to not just what it should be, but how your target audience feels about it.

This is a messier process, one that requires you to get out of the office to engage with these audiences often, instead of just crafting that “perfect” plan on your laptop. For my process, that can mean I:

- Collect and analyze all data available about performance of existing strategies/products/services/websites/etc.

- Review all audience touchpoints and conduct a brand analysis. This is nearly always paired with market research and in some cases, a competitive analysis.

- Collect and review audience data – either internal or external to the organization. A core element to this, which many overlook, is to actually revisit who their ideal audiences actually are. People often go way too broad on this question. As part of my work, we may create audience profiles and/or personas.

- Interview key stakeholders internal to the organization, and other partners in the process. For a larger organization, this means chatting with executives and business leaders, and it (very critically) involves speaking with folks who manage processes day to day, including interns. There are ALWAYS hidden insights about what works for your target audience when you chat with these folks.

- Speak with your ideal audience! This one is huge. I can write a whole series of articles on this one point.

- Consider who else connects you to your audience, and chat with them. Their needs are often complementary, but different. Understanding their needs and goals can be a key difference in serving a community, not just individual goals.

- Commissioning new research, such as surveys, focus groups, etc.

- Test key ideas before you formalize them into an action plan. Too often, we keep our “precious strategy” secret until it is launched. So we only learn what aspects of it work, and which don’t, when it is too late to really adjust. Instead, test ideas again and again to see where theory meets reality.

Inherent in all of this is HUMAN interaction, not some staid list of “best practices.” And empathy is a core part of all of this.

One of my favorite websites is Mixergy.com, where Andrew Warner interviews successful entrepreneurs. What I love about Andrew’s focus is the messy human stuff. So if he is interviewing someone who founded some huge internet company, Andrew always zeroes in on questions about emotions, interpersonal relationships, developing a culture within their organization, the time a customer was let down, dealing with failure, and even how their families coped with the workload required to develop the company.

When you consider all of this within the context of an educational organization, you see the complexity right away: they are serving children, parents, the broader community, and do so with a staff of experts who are aligning to educational standards, internal organizational culture, parental expectations, and let’s not forget: a classroom full of kids! This is not only an incredibly social and human process, but one filled with emotional intensity beyond education itself. Likewise, the “results” of their work (if you can call it that) is not just measured in a short-term letter grade, but in a LIFETIME of actions and experiences that students have once they move on.

For writers I work with, each has the ability to choose every aspect about how they write, how they share that with the world, and how they extend that work into relationships, conversations, or bigger EFFECTS with their audience. And at nearly every step of this process, it is about relationships. I often find that when I begin to work with writers, the first thing we do is try to open that line of communication to readers.

YOUR IDENTITY IS THE EFFECT YOU HAVE ON OTHERS

Identity represents not just who you are, but:

- Why you do what you want to do

- Who you serve

- How you go about doing it

- The potential effect you have on others

- Your long-term legacy, and how you will be remembered

For an author, this can be framed as the moments someone reflects on one of your book 8 years after having read it. For an educator, it how what you taught affects a decision that the former student makes 25 years later.

Maya Angelou has that amazing quote:

“People will forget what you said.

People will forget what you did.

But people will never forget how you made them feel.”

So if I ever talk about “branding,” it is not to limit what someone is, but rather to be mindful of how your actions do or don’t create positive experiences for others. And how that experience can have a ripple effect across a lifetime, even extending to how their behavior effects others. Sometimes we simplify this by calling it “word of mouth marketing,” but it goes so much deeper than that.

With writers I work with, we often go through a process of figuring out WHO YOU ARE (as a writer), and WHERE YOU WANT TO GO (with your work.) Without understanding these things, all other decisions are arbitrary, based on who others are, and where they want to go.

For one successful nonfiction author I am working with now, we are tearing back the layers to really identify where they want their future books to lead. Right now, they are in a crowded niche, and have openly said many times that how their books are defined are not how they define themselves. That’s a big gap to not overlook.

For fiction and memoir authors I am working with, we often dig deep into who they are, why they write, and the effect they hope to have in readers, and use this to craft their bios. I can’t even tell you how interesting this process is.

One client has had this whole intriguing career that not only directly relates to their books, but had previously been hidden from readers. The process we go through isn’t about creating a resume, but crafting a narrative whereby an author’s experience informs readers about their writing and worldview.

I always love Barry Eisler’s bio, which starts:

“Barry Eisler spent three years in a covert position with the CIA’s Directorate of Operations, then worked as a technology lawyer and startup executive in Silicon Valley and Japan, earning his black belt at the Kodokan International Judo Center along the way.”

Would you read a thriller by this guy? Oh, yes you would!

For an organization or company, a lot of this stuff is sometimes framed as a “brand book,” or style guides, and is fully realized in the culture of an organization. While many think a culture can be embodied by a “statement of values” posted on a conference room wall, it isn’t. The culture is what you feel when you walk in a room with these people – and what you feel when you see them doing their work, and engaging with their audience or customers.

Sometimes, you have to look deep into history to experience this. When I worked with Library Journal, I spent time in their archives, looking at issues of the magazine dating back to 1876.

Sometimes, you have to look deep into history to experience this. When I worked with Library Journal, I spent time in their archives, looking at issues of the magazine dating back to 1876.

When you extend this to education, I think the complexity grows, perhaps because the mission is so important. The identity of the institution is embodied in the lives of their students, and it truly becomes a lifelong process to be fully realized.

Perhaps this is why I wanted to dig into the Library Journal archives at the time, to EXPERIENCE their mission instead of having it told to me. And of course, when I look back on my experiences with PS 123 over the years, I reflect on not just what I did with these kids back then, but where they are and what they are doing today:

EVERYONE NEEDS AN OUTSIDE PERSPECTIVE

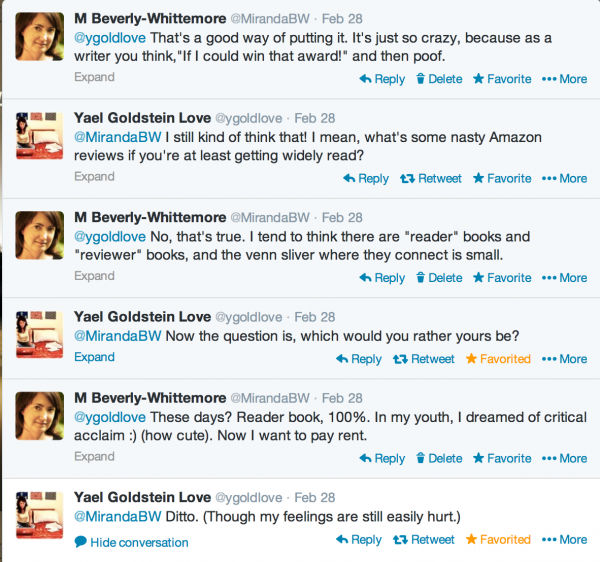

Last night I helped run a local meetup for creative professionals, and we were discussing the challenges someone has in turning an idea into reality. Inherently, there was an issue of stagnation because of how solitary the process can become. And the value of involving others in the creative process. I recently wrote about my process working with Miranda Beverly-Whittemore, and how my role is in some ways to be a “buddy” in the process.

For organizations, having an outside perspective can be critical to not just reframe direction, but also say things that everyone knows, yet remains unspoken. This is nearly always part of my role as an outside consultant – to bring up difficult topics that others avoid because it creates an uncomfortable work environment.

Likewise providing insight into a RANGE of experiences is critical, which is why I love doing work with organizations outside of publishing, even though I often describe my main focus as writers. I feel that responsibility extends outside of the publishing blinders – to understand how public, non-profit, and private institutions establish their voices, craft meaningful work, and connect that work to a powerful EFFECT in the lives of others.

My wife and I recently renovated our home, and I enlisted MANY others in this process, not just to swing the hammer, but to make loads of decisions, to understand boundaries, and explore possibilities. That is what I looked for when hiring a professional – someone whose range of experience created CONVERSATIONS around what is possible, instead of commoditizing the task a list of “best practices” that didn’t take into account our personal goals and challenges.

What is critical for me in considering working with these organizations is to not just READ about their experiences, but to truly dig in and being a part of their challenges, and hopefully, part of the solutions to helping organizations better share their stories and connect with their communities.

Since the experience was like being a kid in a candy store, let’s end with a tour of the Sesame Workshop offices, which was so much fun to explore! (And no, I didn’t get to visit the Sesame Street set, which is located in a separate facility in Queens.)

Many of the walls are coated with chalkboard paint, so the hallways are filled with these murals:

These are actually TVs in the frames, and the characters interact with you as you approach:

My favorite part of this photo is that the emergency exit door in the background (through the glass of the stairs) has an “Exit” sign very low – at Muppet height!

This is a display of Sesame Street educational material from around the world. Amazing to consider how far-reaching the mission of this organization extends.

The kitchen. The coffee-pods kind of freaked me out. I tried not to lose a finger when operating the machine.

The Big Bird inspired cup dispenser:

On the refrigerator:

Office copy machines look the same everywhere:

The incredible view out front: Lincoln Center:

Cubes also look the same in every office building:

Big Bird, Cookie Monster and Grover having a meeting:

The hallway to the CEO’s office suddenly got more formal: wood and glass:

Fun details on nearly every wall:

It’s hard to see, but this lampshade was made of feathers similar to Big Bird’s:

By far the most depressing thing in their offices: the “Cup ‘O Noodles” machine:

Okay, even their bathroom has an amazing view!

Characters, everywhere you look:

Thank you!

-Dan

Sometimes, you have to look deep into history to experience this. When I worked with Library Journal,

Sometimes, you have to look deep into history to experience this. When I worked with Library Journal,

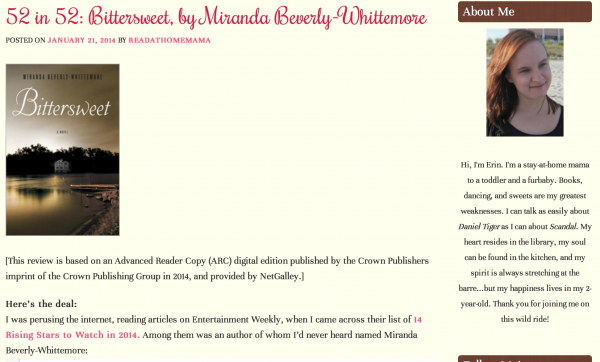

I’ve been sitting on my hands, waiting to share this exciting news with you. Kirkus, one of the most influential reviewers in the book world, has given Bittersweet a starred review.

I’ve been sitting on my hands, waiting to share this exciting news with you. Kirkus, one of the most influential reviewers in the book world, has given Bittersweet a starred review.

My premise- what my novel is “about,” specifically what its moral argument is, and how every moment/character in the novel works in consort with that argument

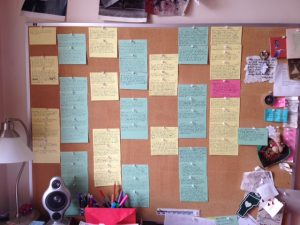

My premise- what my novel is “about,” specifically what its moral argument is, and how every moment/character in the novel works in consort with that argument The book I’m outlining right now has two parallel time periods linked by a narrator (who’s a girl in the past and an elderly woman in the present). I assigned green to the present day, and yellow to the past. Each major character in both past and present was also assigned a distinct color (whenever I wrote a character’s name, I wrote it so that when I lay the cards out, I could visually track how important they are, and keep an eye the “holes” (if any) where they seemingly disappear from the plot (which I find often identifies other weaknesses in a plot).

The book I’m outlining right now has two parallel time periods linked by a narrator (who’s a girl in the past and an elderly woman in the present). I assigned green to the present day, and yellow to the past. Each major character in both past and present was also assigned a distinct color (whenever I wrote a character’s name, I wrote it so that when I lay the cards out, I could visually track how important they are, and keep an eye the “holes” (if any) where they seemingly disappear from the plot (which I find often identifies other weaknesses in a plot).